Although an official census report is not due until October, it appears that the population of our southern resident killer whales has increased by one over the past year. That slight increase is the net result of four births and three deaths, according to the Center for Whale Research, which is responsible for the annual census on July 1 each year.

Until Monday, none of the whales had been seen in Puget Sound since April. So on July 2, CWR biologists traveled out to coastal waters and were able to locate and identify all 74 orcas they had hoped to find, said Michael Weiss research director for CWR. The five-day trip turned out to be highly productive, he said, adding that details will be reported in a series of encounter reports to be published on the center’s website.

“Everybody is out there,” Michael told me, expressing relief that no other whales had died since they were last observed in Puget Sound two months ago. “Getting the census was our first task,” he added, “followed by monitoring their health condition.”

Michael acknowledged that he was worried that one or more of the endangered whales might not be found, possibly adding to the death count. “It was a little nerve-wracking at first,” he said, “then we ticked the whales off one by one. The last few were older females.”

Two of the deaths to be reported in the 2025 census are young whales that didn’t make it past their first year of life. Consequently, the two will show up as both births and deaths in the census report, to be submitted to the federal government by Oct. 1. The third death involved a 31-year-old male named Lobo, or K26, reported missing last October.

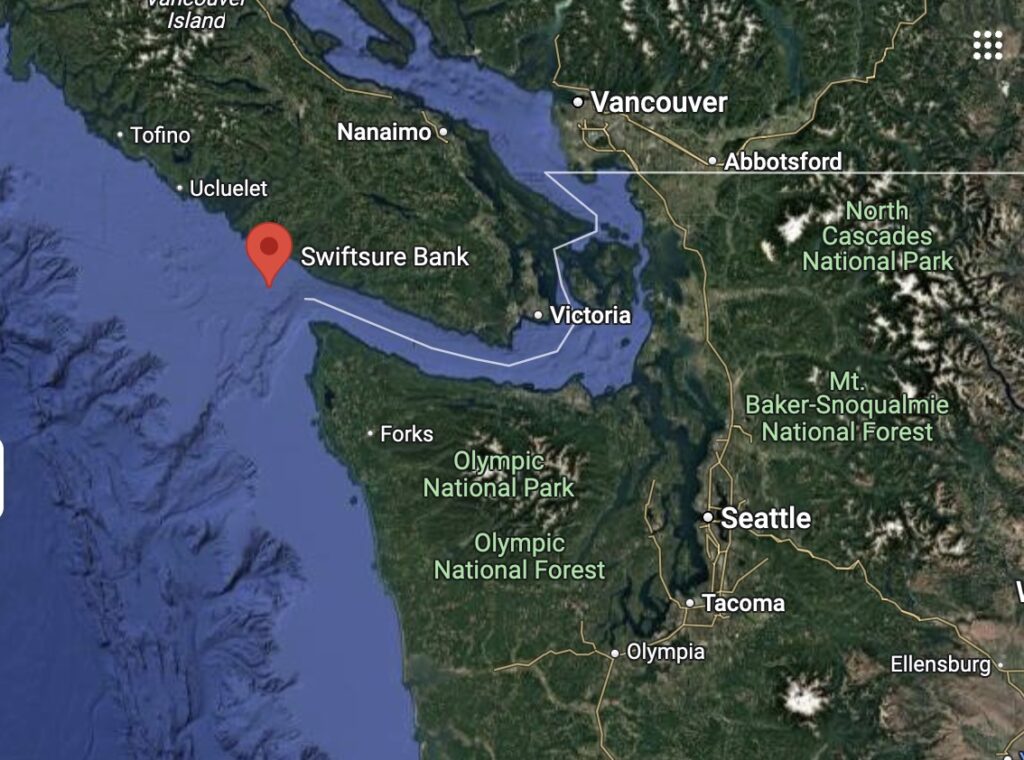

Two whales born during the census year have survived, and CWR biologists found the two calves among the southern residents gathered earlier this month at Swiftsure Bank near the entrance to the Strait of Juan de Fuca. One calf is J62, a female first seen in December with her mother, J41, a 20-year-old named Eclipse. The other is J63, also a female, first seen in April with her mother J40, a 21-year-old orca named Suttles.

“Nothing we saw with the two calves made us worried,” Michael said, noting that an unfortunate number of southern resident calves don’t survive to their first birthday. “They looked fine. They were playing with each other, which was cool to see. We are hoping they are over the (survival) hump now.”

The official census for the southern residents is expected to report 74 whales in 2025, up from 73 last year, as I reported in Our Water Ways in October. The census work is conducted under contract with the National Marine Fisheries Service.

Food is the key

One cannot help but ask why the orcas have been missing from Puget Sound for so long and why they would choose to congregate in an area along the west coast of Vancouver Island just outside the Salish Sea. Scientists say the answer no doubt has everything to do with food.

Chinook salmon are the preferred prey of the fish-eating southern residents. Historically, they have been able to find sufficient spring- and summer-run Chinook in Northern Puget Sound and Southern British Columbia from early spring into late summer. That’s when the fish are returning to Canada’s Fraser River and Puget Sound streams, such as the Skagit and Nooksack. Through the years, declines in the Puget Sound runs have meant a greater reliance on Fraser River stocks — but now even those are in serious decline.

“The whales are making a calculation that fishing is better out there than in here,” Michael said, explaining why the orcas would choose Swiftsure Bank over Puget Sound waters. “The data I’ve seen and the word from sport fishermen is that there are a lot of different fish out there: Columbia River fish, Puget Sound fish, Fraser River fish, West Coast Vancouver Island. It’s a geographic bottleneck for a lot of different stocks.”

Among all the Chinook, the Fraser River fish are often larger and fattier, he said, which is why they may be preferred, at least when available. It is the availability of the salmon that has dramatically changed the movement patterns of the orcas over the past decade or more, he said.

The struggle to find food has had an impact on the population’s overall health, according to a variety of experts, including the research group SR3, which uses drones to photograph the whales from above to produce a general health assessment of each animal. The group’s latest update, issued in June, showed a continuing decline in body condition among the southern resident killer whales, with nearly a third of the animals considered in poor condition for the second year in a row.

“SRKWs found to be in poor body condition have an elevated likelihood of mortality, making it imperative that SRKWs have access to an adequate supply of prey throughout the year,” said Holly Fearnbach of SR3 in that update.

New boating regulations

In recent years, SR3 health assessments have resulted in emergency boating regulations to protect the southern residents from noise and interference that might disrupt their hunting activities. The emergency rules, issued by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, required boaters to stay 1,000 yards from the whales. Now, that 1,000-yard rule is permanent and year-round, the result of a 2023 law that went into effect in January. (See Our Water Ways post.) The law applies to recreational watercraft, including kayaks and paddleboards, as well as commercial whale-watching boats.

“Southern Resident killer whales rely on sound — echolocation — to find food, and the noisy waters of Puget Sound can mean missed meals and hungry whales, especially during peak boating season,” said Julie Watson, WDFW’s killer whale policy lead, in a news release. “When boaters avoid the whales and stay at least 1,000 yards away, they are immediately helping increase these whales’ ability to forage and communicate with each other.”

Julie reported that when the orcas return to Puget Sound, enforcement officers with WDFW will be stationed in the vicinity to educate boaters and enforce the new rules.

On Monday, J pod was seen swimming north in Haro Strait along the west side of San Juan Island, according to Monika Shields of Orca Behavior Institute. “Welcome home, J pod,” she said in her blog post, which features a photo of J39, a 22-year-old male named Mako.

The whales continued north through Active Pass into Canada’s Strait of Georgia, according to Serena Tierra, who compiles whale-sighting reports for Orca Network. The whales headed back south yesterday and were heard on a hydrophone last night in Haro Strait. A Facebook group in Sooke, B.C. (the south end of Vancouver Island), reported 20 or more southern residents in the Strait of Juan de Fuca at 9:45 a.m. today, Serena told me in an email, “so it looks like they are leaving for now.”

When will J pod return to Puget Sound and possibly be joined by K and L pods? Even the best orca experts are loathe to guess. Less uncertain, I would say, is that J pod — the one pod considered most “resident” in Puget Sound — is scouting around to check out the current availability of Chinook salmon or even coho and chum salmon. Southern residents are known to prey on coho and chum in Central and South Sound during the late summer and through the fall, after the Chinook have entered their home streams.

The preseason salmon forecast produced by WDFW and area tribes calls for a 32-percent increase in Puget Sound Chinook over the recent 10-year average run size. It is also up 9 percent from last year’s forecast. The increase is attributed to greater hatchery runs, since the number of wild Chinook is actually predicted to be down this year.

State fishery managers and biologists say the current run appears to be within the range of the forecast, but it is too early to know for sure, since commercial and sport harvest numbers have yet to be compiled. Early fisheries show lower catch rates in some areas but higher in others, they say.

Meanwhile, coho runs are expected to be up slightly, although mostly attributed to hatchery fish. As for Chum, which had good runs last year, the number of hatchery fish is expected to fall below the 10-year average, yet the number of wild fish may be up 35 percent to create a fairly strong run.

New reports contribute to discussions

A new study by researchers within Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans examines how an increase or decrease in Chinook runs could affect the trajectory of the southern resident population, currently headed toward extinction.

The study employs a computer model, which predicts a 4.7 percent decrease in the orca population by 2050 if current conditions are allowed to continue, states a pre-publication (not yet peer reviewed) paper in the online journal Social Science Research Network. On the other hand, if all Chinook populations were to double, the orca population could grow by 9 percent in the next 25 years.

The paper stresses the importance of focusing on specific salmon stocks. For example, if four-year-old Fraser River summer Chinook were to increase five-fold from recent lows, the killer whale population could more than double (a 101 percent increase). But the population could at least swing into a growth pattern with a 40 percent increase in four-year-old spring Chinook in the Fraser along with a 9 percent increase in Columbia River spring Chinook.

“The results of this study align with the finding that not all Chinook salmon stocks contribute equally to the SRKW diet,” state the authors, including Sheila Thornton, head of the Marine Mammal Conservation Physiology Program at DFO. “Our results indicate that the abundance of spring and summer Fraser River Chinook salmon could have played a key role in limiting the growth of the SRKW population over the last 40 years…. Further, the results of the present study reinforce existing knowledge of SRKW movements linked to the spaciotemporal availability of their preferred prey.

“Future management actions should consider the importance of individual Chinook salmon stocks to SRKW and develop recovery measures based on stock-specific life history strategies, migration patterns, survival rates, and size- and age- at-maturity,” the document states.

Another new report, titled “Strengthening recovery actions for southern resident killer whales,” offers recommendations from more than 30 scientists involved with orcas, salmon and related fields, including acoustics and toxic chemicals.

The report, following a March workshop organized by conservation groups, concludes: “Prey limitation remains the primary constraint on SRKW recovery, and the panel deemed current government initiatives on both sides of the Canada-US border to address this issue to be insufficient…

“Undersea noise emanating from anthropogenic sources continues to pose a significant impediment to the population’s recovery, exacerbating the impact of prey limitation by interfering with echolocation and successful foraging. Consequently, the panel recommended the prompt finalization and implementation of meaningful underwater noise-reduction targets that are biologically relevant to SRKWs,” the report continues.

The third factor addressed with specific recommendations involves toxic contaminants, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), that still plague the orcas.

Michael Weiss, a participant in the workshop, said what stands out to him from the discussion is an understanding that, while hatcheries may have a role in providing larger numbers of fish, they don’t produce the best fish for killer whales, because hatcheries tend to produce smaller fish with different behaviors that don’t meet their needs like wild fish.

Michael said he also supports a suggestion to move the fishing grounds closer to the streams (terminal areas) where adult salmon are returning. That would not only give the whales the “first crack” at the fish, he said, it would better allow for the protection of wild salmon stocks most at risk of extinction and thus encourage the natural production of larger fish.

Needed changes may not come all at once, Michael said, but policies must be revised if we hope to save the orcas from extinction.

“As biologists and ecologists, we try to be clear about the uncertainties,” he said, “but politicians don’t want uncertainty. The information gets lost in translation. Still, there is overwhelming evidence that if we stay with the current situation, the whales will continue to decline.”