Investigating PCB, PBDE, and dioxin & furan hotspots in the Hylebos, Blair, and Sitcum Waterways

Over the past several decades, Commencement Bay has seen major improvements thanks to more than $600 million invested in cleanup and restoration by industries and agencies. Sediment dredging, capping, and upgrades to wastewater and stormwater systems have reduced pollution and lowered contaminant levels in the environment and marine life—for example, PCB levels in English sole are now approximately 80% lower than levels measured 40 years ago.1 These are important successes. At the same time, recent monitoring shows that certain areas of Commencement Bay, especially the Hylebos, Blair, and Sitcum Waterways, still have elevated levels of contaminants, such as PCBs, PBDEs, and dioxins & furans. In some cases, concentrations have rebounded following sediment dredging, raising questions about whether ongoing sources are reintroducing contaminants. To address this, new studies led by UW Tacoma’s Center for Urban Waters and the Port of Tacoma will track down remaining hotspots, with the goal of providing actionable information to guide future cleanup and protection efforts.

Please feel free to share the project factsheet.

Toxic legacies: why these pollutants matter

Even though the intentional production of PCB, PBDE, and dioxin & furans was banned decades ago, these pollutants remain in the environment, potentially impacting fish, shellfish, and people. This is especially concerning for Tribes, including the Puyallup Tribe of Indians and the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe, who have deep cultural and nutritional ties to salmon and shellfish harvests.

PCBs were widely used in electrical equipment, building materials, and other products until they were banned in the late 1970s. They do not break down easily and build up in the bodies of fish, shellfish, and humans.

- Human health: PCBs are known to cause cancer in people and can damage immune, reproductive, and nervous systems. In Commencement Bay, the Washington Department of Health advises against eating crab, shellfish, or bottom-feeding fish and suggests limiting how often people eat salmon due to PCB contamination.2 People can also be exposed to PCBs through the air.3 & 4

- Environmental health: In marine life, PCBs can interfere with hormones, weaken immune defenses, and reduce survival. Studies show that juvenile Chinook in the Hylebos Waterway carry some of the highest PCB levels in Puget Sound, and are high enough to impact Chinook health and survival.5

PBDEs are flame-retardants once widely used in everyday products such as furniture, textiles, and plastics. Although phased out of most products over a decade ago, they continue to enter the environment from older materials, where they persist for some time.

- Human health: While research is ongoing, the EPA classifies PBDEs as possible human carcinogens.6 & 7 Breathing contaminated air is one of the pathways that can expose people to PBDEs.8

- Environmental health: Even at low levels, PBDEs can affect young salmon by disrupting hormones and making them more vulnerable to disease.9, 10, & 11

Dioxins and furans are highly toxic byproducts created during industrial processes such as waste burning, chemical manufacturing, and historically, paper bleaching. They remain in the environment for decades once released.

From Bay to biota: where is there contamination?

For decades, numerous agencies and organizations have monitored contaminants in Commencement Bay and the marine life that live there. Despite significant clean-up efforts, recent surveys show that juvenile Chinook and English sole in the Hylebos carry some of the highest PCB levels in Puget Sound.1 Mussels and crab in the area also show elevated PCBs.14 & 15 Additionally, PBDEs are high in juvenile Chinook and mussels throughout the Bay, particularly in the Hylebos, Blair, and along the northeast shoreline.5 Recent water quality monitoring by the Department of Ecology confirmed that the Hylebos is a clear hotspot for PCBs and PBDEs.5 While the Port of Tacoma detected dioxins & furans above screening levels in parts of the Blair Waterway.5 This suggests there may be ongoing sources that are recontaminating the waterways.

Our studies will build on this foundation to better understand where and how these pollutants are entering Commencement Bay and the marine food web. To start, we brought together researchers, experts, and local stakeholders at a symposium in May to share insights from past monitoring and strengthen our hotspot tracking efforts.

Put on your detective hats: we’re tracking down hotspots

The University of Washington Tacoma’s Center for Urban Waters and the Port of Tacoma’s complementary studies focus on identifying more specific contaminant hotspots. Together, these efforts will investigate multiple pathways—including air, stormwater, and sediments—across the waterways and their surrounding drainage basins.

All analyses will include congener-level measurements, allowing researchers to track specific chemical fingerprints and better understand their sources and impacts.

Air deposition

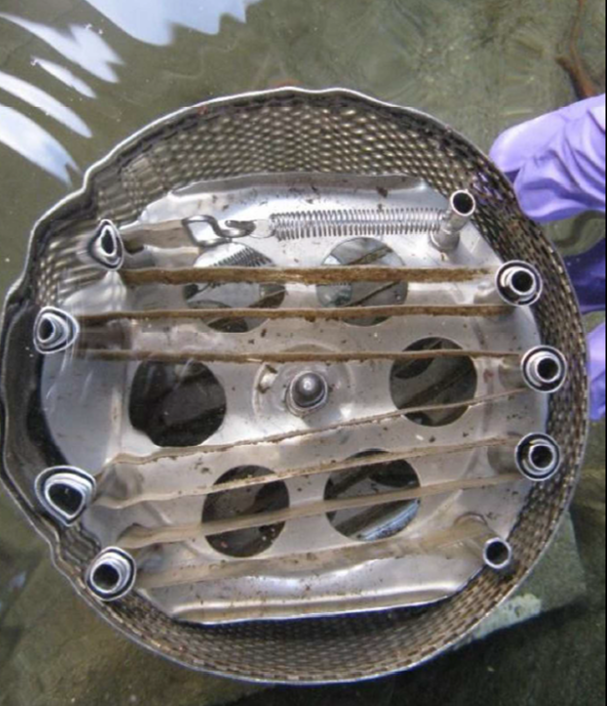

Around the world, studies show that air emissions from industrial activities can be a source of PCBs and PBDEs to surface waters, with implications for both ecosystem and human health.16 & 17 To assess this locally, we will construct air sampling units following methods developed by King County.18 & 19

Water column

Recent Ecology monitoring identified the Hylebos Waterway as a hotspot for PCBs and PBDEs.5 By deploying additional passive samplers in the water column, we can refine our understanding of where contaminants are entering the Waterway from the surrounding watershed.

Sediment flux

In some cases, pollutants can move back and forth between contaminated sediments and the overlying water.20 While remediation has reduced contamination in many areas, some sediments still have elevated levels. We will supplement bulk sediment sampling with sediment flux samplers, which provide estimates of both contaminant movement and the bioavailable fraction that can be taken up by marine life.21

Co-deployment with mussels

The Port of Tacoma is partnering with the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife Mussel Watch, which uses mussels as a sentinel species for contamination. They will deploy mussel cages alongside sediment traps and passive water samplers, creating a fuller picture of bioavailability and source pathways. These sites will also test for dioxins & furans.

First round of monitoring

We deployed our first round of samplers in December and January at the following sites.

Expert insights shaping the investigation

Over the last several decades, Commencement Bay has seen extensive clean-up and monitoring involving a range of groups, agencies, and jurisdictions. Collaborators along the waterways such as the Puyallup Tribe of Indians, regulators, industry, and community-based organizations can offer invaluable context and insights into potential hotspots. Many of these groups have generously joined a Technical Advisory Committee to help:

- Access and integrate existing monitoring data to inform our sampling strategy

- Iterate on the proposed monitoring locations based on suspected sources, historical clean-up activities, and our preliminary results

- Interpret and apply results to develop management recommendations, and build buy-in for future implementation of those actions

If you’re interested in staying informed, please email Marielle (marlars@uw.edu).