How do we effectively manage nutrients to support healthy marine life in Puget Sound?

Our region is navigating complex decisions on how best to manage nutrients – specifically nitrogen – to maintain healthy habitats. Additional nitrogen from human activities can potentially increase harmful algal blooms, decrease dissolved oxygen, compound ocean acidification, and cause other changes that may harm marine life. New regulation is particularly focused on the impacts that nitrogen from human sources has on low dissolved oxygen in Puget Sound. The nutrient management decisions we make now have the potential to shape the future of wastewater treatment, water quality, and our communities for decades to come.

Looking for a quick policy-focused overview?

Explore key scientific insights and tradeoffs to support strategic nutrient management decisions in our

StoryMap.

Puget Sound Institute is advancing science to inform nutrient management

For the past several years, the University of Washington Puget Sound Institute has played a central role in advancing the science and modeling that underpin nutrient management decisions in the region, including:

Leading cutting-edge research on species-specific risks that integrates temperature-dependent oxygen supply and demand.

Hosting a series of workshops to build consensus and accelerate scientific progress.

Convening an international Model Evaluation Group and leading ongoing model performance assessments.

Running the Salish Sea Model to test additional nutrient reduction scenarios.

Sound-wide oxygen levels are generally healthy, but do changes in Hood Canal and embayments pose a risk to marine life?

Regulation is particularly focused on the impacts that nitrogen from human sources has on low dissolved oxygen in Puget Sound. A few key scientific insights help ground these management decisions:

- The right combination of sunlight and nitrogen can cause algal blooms. Algae support the base of the food web, but when they die and decompose, they can cause low dissolved oxygen.

- While most of Puget Sound has sufficient levels of dissolved oxygen throughout the year, low dissolved oxygen occurs naturally in some places.1

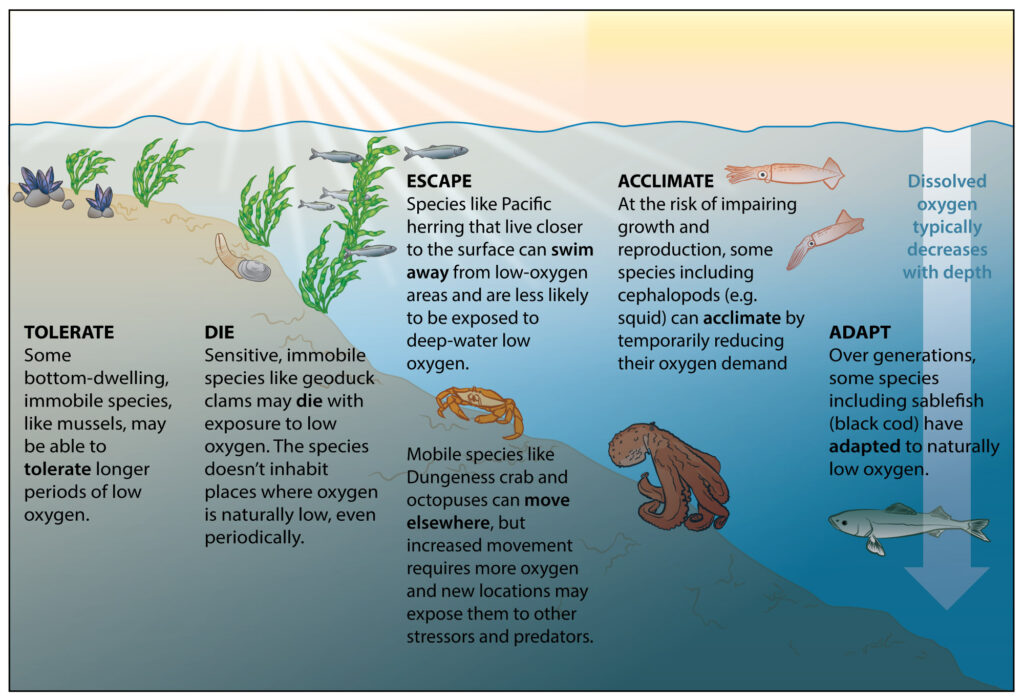

- Not all oxygen declines are necessarily harmful. Marine life may escape, acclimate, or adapt to mild drops in oxygen, but more severe or prolonged exposures may lead to stress or death.

- Although just 9% of the nitrogen in Puget Sound comes from human sources, modeling suggests it can worsen low oxygen conditions, particularly in Hood Canal and some shallow embayments.1

Where do nutrients come from and is that changing?

-

- About 2% of nitrogen inputs are from watershed sources such as agriculture, stormwater, and other diffuse human activities.

-

- Research by Dr. Gordon Holtgrieve and Elizabeth Elmstrom found that δ¹⁵N ratios in the Deschutes and Nooksack Rivers indicate anthropogenic nitrogen inputs, while most other rivers show isotopic signatures dominated by natural soil and forest sources—potentially linked to alder succession and legacy forestry practices.9

-

- Deep ocean water entering Puget Sound is naturally low in oxygen and high in inorganic nitrogen, delivering large daily loads. While much of this nitrogen exits on the ebb tide, a fraction mixes upward, fueling phytoplankton productivity.

-

- Over the past four decades, oxygen at the shelf break has declined by ~20%, altering the quality of water entering Puget Sound.10 With climate change, even small shifts in the depth of this exchange flow could have major effects on Sound-wide nutrient and oxygen conditions.

Nutrient inputs and primary productivity remain relatively stable

Nutrients feed algal blooms, which support the base of the food web, but can also cause low dissolved oxygen. Interestingly, primary productivity in the Salish Sea has remained stable for several decades. Using nitrogen budgets and sediment isotope analyses, Dr. Sophia Johannesen (Fisheries and Oceans Canada) found that total productivity has changed little since the 1970s. However, the composition of phytoplankton appears to be shifting—from diatoms to dinoflagellates—in some basins.6

Focusing on temperature & oxygen jointly may better protect marine life

As Professor Tim Essington explains, warmer water holds less oxygen while also increasing how much oxygen marine species need to thrive.

University of Washington researchers analyzed more than 12,000 shipboard measurements and identified five sites with sufficient data to track century-scale trends. Over the past century, warming caused most of the 0.3–0.9 mg/L decline in fall, bottom-water oxygen at several long-term monitoring sites in Puget Sound – near Seattle, Point Jefferson, and Carr Inlet.4

At our 2022 workshop, Martha Sutula shared how the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project is jointly modeling temperature and oxygen to understand risk and inform management actions in California. University of Washington scientists are similarly studying temperature and oxygen to identify when and where species in Puget Sound are most vulnerable.

If warming trends continue, climate change could also erode gains from reducing nitrogen inputs to the Sound. For example, in the Chesapeake, temperature increases are expected to offset 6-34% of improvements from the last 40 years.6

Modeling is driving nutrient management

Washington State uses both Salish Sea Model outputs and measured data to determine 303(d) listings of impaired water bodies. Under the presumptive water quality standards, a specific location in Puget Sound is considered non-compliant on a given day if:

- Measured oxygen levels fall below either the numeric criteria (4 to 7 mg/L) or modeled estimates of natural conditions, whichever is lower. AND

- Modeled results show that human activities reduce oxygen by more than 0.2 mg/L or 10% below natural conditions, whichever decrease is smaller

Most of Puget Sound falls below the numeric criteria even without human impacts, so it is important to consider natural conditions. How we draw the line matters—particularly since most noncompliant areas barely exceed the standard.8

Nutrient targets are informed by model results

Model results released in June 2025 underpinned the Draft Puget Sound Nutrient Reduction Plan, Washington’s advanced restoration strategy for meeting marine dissolved oxygen standards. The State ran several scenarios to explore the potential impact of reducing nutrients from marine point sources and watersheds. Proposed nitrogen loading targets were ultimately derived from the Opt2_8 modeling scenario in Figueroa-Kaminsky et al. (2025) and would reduce anthropogenic:

- Watershed nitrogen loads by 53-67% region-wide, and up to 90% in some areas.

- Marine wastewater treatment plants by 68% overall. This includes:

- Capping industrial facilities, small wastewater treatment plants, and plants discharging to Admiralty Inlet, Hood Canal, the Strait of Juan de Fuca, or the Strait of Georgia at 2014 loads.

- Limiting effluent from other wastewater treatment plants to 3, 5, or 8 mg/L, depending on the specific plant and season.

Based on feedback during the public comment period, the State decided additional work is needed before finalizing the Puget Sound Nutrient Reduction Plan.

Model uncertainty limits regulatory confidence

In 2023-2024, Puget Sound Institute convened global experts to advise on how to improve the application of the Salish Sea Model to inform recovery goals and nutrient management decisions in Puget Sound. More recently, Puget Sound Institute reviewed Figueroa-Kaminsky et al. (2025) to evaluate how the model updates and analyses influence the proposed nutrient targets. Our analysis reinforced that:

- Model performance across the Salish Sea is comparable to other models used nationally to set nutrient and water quality standards. However, to our knowledge, Washington is the only state that also relies on modeling—not just monitoring—to determine 303(d) non-compliance.

- The State made thoughtful refinements that improved model skill and advanced several of the Model Evaluation Group’s recommendations, but model skill may be reaching its practical limits.

- While model skill has improved, errors in embayments remain several times higher than the 0.2 mg/L human use allowance used to define compliance.

- Additionally, the subtraction of two scenarios may not cancel uncertainty—especially since the reference condition cannot be validated.

Credibly implementing Washington state’s standard may require model skill beyond what any model can likely ever achieve. 9

Complex environmental challenges benefit from insights and ongoing advice from scientists in other regions like the Chesapeake Bay and the Baltic, where models have been used to manage nutrients for decades. The University of Washington Puget Sound Institute convened global experts to advise on how to improve the application of the Salish Sea Model to inform recovery goals and nutrient management decisions in Puget Sound. We were lucky to benefit from the expertise of Bill Dennison, Jacob Carstensen, Jeremy Testa, Kevin Farley, and Peter Vanrolleghem.

The following technical memorandum reviews the information provided in Figueroa-Kaminsky et al. (2025) to evaluate how presented model updates and analyses influence the proposed nutrient targets.

Additional management scenarios

Puget Sound Institute has complemented the State’s modeling to run additional scenarios to assess the magnitude of change in dissolved oxygen concentrations from changing specific wastewater treatment plant and river loads, including:

By sharing our model analysis and postprocessing scripts, we hope to spark robust scientific discussion and co-development. Other models like LiveOcean and SalishSeaCast also help deepen our scientific understanding to inform management actions.

Want to dig into the details further?

Explore our scientific workshops

Our scientific workshops build on regional discussions like Ecology’s Nutrient Forum and the Marine Water Quality Implementation Strategy to dig deeper into uncertainties like the “memory” from sediment oxygen demand and different species’ vulnerability to dissolved oxygen. We appreciate everyone’s generosity with their time and the valuable insights shared by numerous monitoring experts, modelers, managers, and researchers.

Modeled and historical monitoring insights on water quality differences throughout Puget Sound 02.12.25

Explore the recording, slides, and summary

- Kickoff: The Science of Puget Sound Water Quality 7.26.22 Slides | Summary

- Tools to Evaluate Water Quality 9.29.22 Slides | Summary

- Biological Integrity of Key Species and Habitats 10.06.22 Slides | Summary

- Sediment Exchange 10.17.22 Slides | Summary

- Phytoplankton & Primary Production 12.06.22 Slides | Summary

- Watershed Modeling 12.12.22 Slides | Summary

Read Puget Sound Institute’s nutrient articles.

Have a question or interested in collaborating?

Email Stefano Mazzilli (mazzilli@uw.edu) and Marielle Kanojia (marlars@uw.edu).