Kayaker-scientist Brian Footen is back on the waters of Puget Sound this summer, paddling through inlets and circling islands on a 2,700-mile journey to photograph the shoreline and document natural and human-caused changes to the habitat.

This state-funded project is Brian’s second photographic trip along the sinuous shoreline throughout the entirety of the Sound, from Budd Inlet in the south to the San Juan Islands in the north, as well as the Strait of Juan de Fuca and Hood Canal. When conditions warrant, Brian uses a motorized skiff or inflatable raft, especially where strong currents impede his travels.

The project, which contributes information for protecting shorelines and restoring more natural conditions, received overwhelming support from the Legislature when it was approved two years ago.

Brian, 59, who worked more than 20 years as a fisheries biologist, got an early start on the project with no state funding when he launched his first company FishViews in 2014 and began photographing the lower Elwha River two days following final dam removal.

Brian’s first state-funded trip, from 2023 into 2024, resulted in more than 433,000 photographs, showing every sort of shoreline feature — from sandy beaches and towering bluffs to bulkheads, boats and buildings in various states of structural integrity.

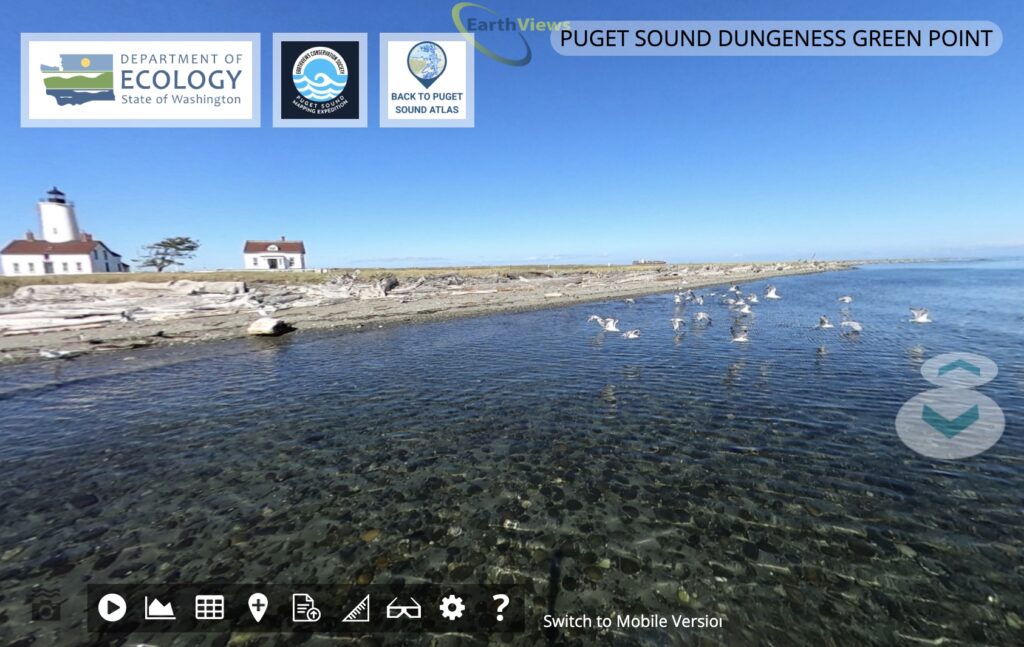

The first set of water-level photographs was recently incorporated into Washington Department of Ecology’s Shoreline Mapping System, which already included photographs taken from low-flying aircraft to provide a natural perspective of the landscape. These new water-level images of Puget Sound, incorporated into a Puget Sound Atlas, have added significant detail to enhance our understanding of the entire shoreline.

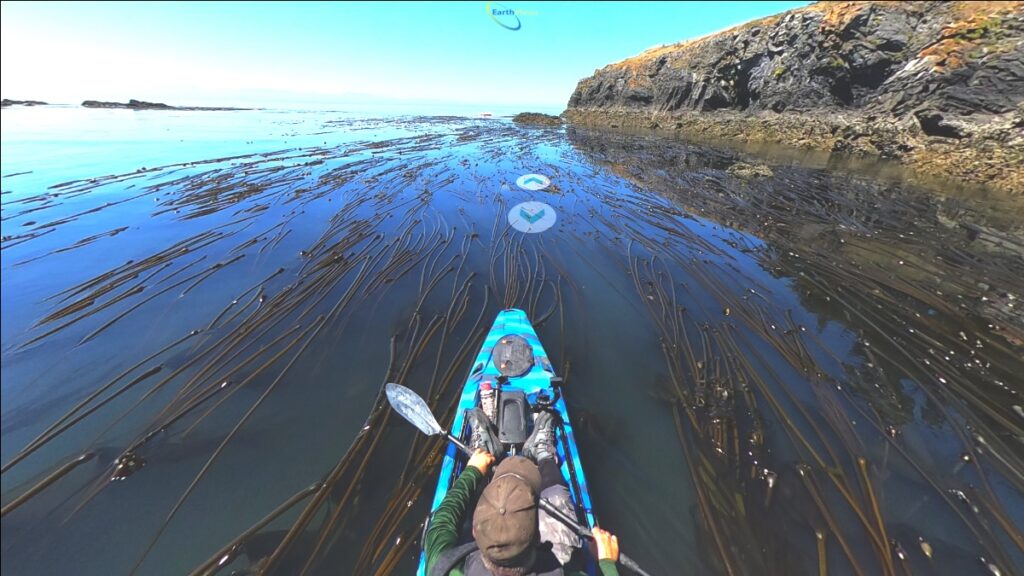

Using the related map, anyone with an internet connection can visit nearly any shoreline location or even take a kayak “tour” along the edge of the water. The EarthViews platform — akin to “street view” in Google Maps — allows users to stop anywhere along the route and take a 360-degree look-around.

The images originate with a special 360-degree camera mounted on an 8-foot vertical pole attached to the back of the kayak. Typically, Brian sets the camera to shoot a picture every 10 seconds as he paddles at a steady pace of 2-5 miles per hour, staying some 15 feet from the shore. Because of tides and the need to operate during daylight hours, Brian often paddles six hours a day.

At times, the daily excursions on Puget Sound can be challenging, particularly in strong currents or when submerged rocks present a clear hazard. But when the waters are calm and deep, Brian may allow his mind to drift.

“There are times when you get into kind of a Zen zone, taking everything in and enjoying the sounds of the waves,” he told me.

In mid-June, Brian and his partner Rob Crampton — who together run the nonprofit group EarthViews Conservation Society — launched this year’s venture in Boston Harbor near Olympia heading south and passing houses, boats, docks and other structures. The weather has been dry of late, Brian noted, but travel has been challenging because of tides and winds.

“We are seeing a lot of baby seals, marine birds and eagles working hard to swoop them up,” Brian wrote in an email. “Egg jellyfish have been abundant, and we have come across the occasional school of juvenile salmon.”

The plan is to cover the entire shoreline from Olympia to Shelton by the end of July, then head up to the San Juan Islands, where the project will be based on a 46-foot research vessel with live-aboard facilities. After that, it will be on to Hood Canal and Whidbey Island, followed by the remainder of Puget Sound during the winter.

Legislative funding

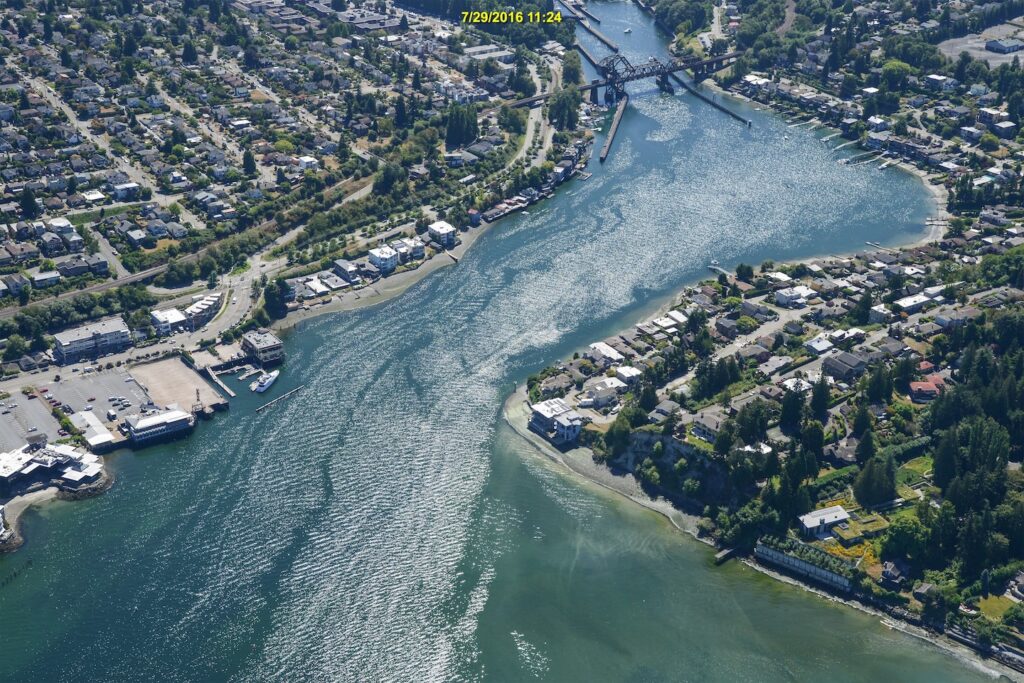

In 2023, the Washington Legislature authorized an ongoing program to photograph and assess the condition of the entire Puget Sound shoreline every two years at a cost of about $2.2 million per biennium. The legislation, supported by state agencies and environmental groups, calls for both aerial and on-the-water photography, as well as a shoreline condition assessment.

State Sen. Jesse Solomon, D-Shoreline, the prime sponsor of the bill, said the ongoing survey will help identify where ecological damage is taking place. The photographs provide sufficient detail to identify suitable habitat for forage fish, salmon, orcas and marine birds, he said. Such photographs also can help prioritize locations where restoration would be most effective.

“We need an accurate and up-to-date baseline survey of marine shorelines to understand where development has occurred and to prioritize restoration and protection actions, and to help with local planning implementation,” Solomon said during the bill’s first hearing before the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Water, Natural Resources and Parks.

Amy Carey, executive director of Sound Action, said the survey can help more people understand the problems facing salmon, which are especially vulnerable when they leave the streams as juveniles and swim along the shore. It is essential that they find prey and protective habitat to get a good start in life, she said, and the shoreline photos help tell the story of their survival.

“We currently have information gaps that are severely limiting the effectiveness of public and private actions to recover the marine food web that is so critical to these juvenile salmon,” said Carey, whose organization is focused on the preservation of the nearshore habitat. Salmon, of course, are essential prey for the endangered southern resident orcas, she added.

Don Gourlie, legislative policy director for the Puget Sound Partnership, said shoreline surveys can be used by state and local officials tasked with protecting the habitat. Even before visiting a site in person, officials can gain an understanding of the surrounding conditions, he said. One can also estimate how proposed developments or restoration projects contribute to the “cumulative impacts” or to improvements in the ecosystem.

City, county and tribal governments can access the images and data to help with shoreline planning, determining the environmental effects of specific projects and identifying unpermitted construction. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife can use the information for shoreline permitting, and Washington Department of Natural Resources can seek out derelict boats and creosote pilings that can harm sensitive species.

The Department of Ecology has been conducting shoreline photography and mapping since the Shoreline Management Act was passed in 1972, but funding has always been an issue, said Hannah Drummond, a shoreline mapping scientist for the agency. The Legislature’s commitment to an ongoing, systematic program opens the door to a better understanding of long-term shoreline changes.

“That’s what I love about it,” Hannah said. “It is so rare that there are funds for a long-term monitoring and mapping project, updated every two years forever, and this will get better over time.”

As global warming brings sea-level rise, shoreline changes could become dramatic in some places, she added, and this enhanced effort will document those changes as well as habitat alterations caused by human development and even restoration projects.

Both the water-level and off-shore aerial photographs involve building an extensive collection of overlapping photos covering every foot of the shoreline. The images are then processed, mapped and added to user-friendly websites. Of the two-year, $2.2 million legislative appropriation, about $250,000 goes to the water-level portion of the project, with about $600,000 to the aerial portion. Another $440,000 goes into collecting additional vertical imagery for the required shoreline condition survey. The remainder of the funding goes to Ecology scientists and staff who compile and assess data, write survey reports, manage contracts and conduct other administrative duties.

On final passage, only one legislator voted against the bill creating the ongoing shoreline survey. Misgivings about the potential for invading people’s privacy were addressed with an assurance that any incidental pictures of people, boat registration numbers and other sensitive information would be blurred before publication.

An amendment added to the original bill requires the Department of Ecology to keep records whenever any information from the mapping program is used in a civil or criminal investigation. So far, four cases have been logged into that record system, according to Ecology spokesman Curt Hart.

A lifelong interest

At age 12, Brian’s interest in marine biology was a sparked by a visit to Shedd Aquarium in Chicago, where he was living with his mother at the time. His interest in marine life grew, and he later attended the University of Washington, dropping out to work for four years on a commercial fishing trawler in Alaska. With encouragement from his aunt in Tacoma, he returned to school and attended The Evergreen State College in Olympia.

Brian was hired as an intern by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Washington state and then took a job with the Point No Point Treaty Council as a fisheries biologist. In 1996, he became a research biologist for the Muckleshoot Tribe in Central Puget Sound while completing a dual master’s degree in fisheries science from Evergreen and the UW.

After 20 years as a fisheries scientist, he said, “it got to the point where I was kind of looking for another path and a way to help aquatic species on a larger scale.”

About that time, Brian was floating the Green River and counting salmon nests, or redds, as part of an effort to estimate fish populations. When he heard a high-pitched drone flying nearby, it occurred to him that a person might be able to see streams more clearly and easily from a remote-controlled aircraft. He called a friend, Scott Gallagher, a former Navy pilot, and they began flying drones along rivers to assess environmental conditions. The project had mixed success, sometimes with the aircraft crashing into trees.

Using Google Maps to scout out locations, Brian stumbled upon a “street view” from a bridge over the Duwamish River — the lower portion of the Green River. In the application, he could virtually turn and look over the side of the bridge onto the water.

“That’s when the light bulb went on for me,” Brian said, recalling the moment. “Let’s do a ‘street view’ of the river!”

Footen and Gallagher soon launched a new company called FishViews with financial help from friends and family. Rob Crampton, an environmental engineer who had worked on the drone project, fashioned an apparatus that could provide a 360-degree view by stitching together images from six GoPro cameras aimed in different directions.

In a partnership with Environmental Systems Research Institute, or ESRI, the new company was able to integrate location data into ESRI’s GIS-based mapping system. By 2017, the computer-based platform was ready for full-scale operation when, fortuitously, GoPro introduced a new 360-degree camera. The GoPro Max 360, with two wide-angle lenses aimed in opposite directions, was quickly incorporated into the system to provide full-circle images wherever it went.

Over the next three years, FishViews covered 10,000 miles of rivers and shorelines throughout the U.S. and in Africa before the COVID-19 pandemic shut everything down. That’s when Brian and Rob adopted a conservation angle and began supporting the effort with donations and various grants to map the Great Salt Lake, Lake Meade and Lake Tahoe in Utah, Nevada and Arizona.

In January 2023, the two partners formally created a nonprofit corporation called EarthViews Conservation Society after divesting from the separate for-profit company, which had taken the name EarthViews.com, renamed from FishViews. EarthViews .com, now headed by CEO Courtney Gallagher, remains a key part of the operation, processing data and images generated by EarthViews Conservation Society to create the complex mapping system.

Puget Sound observations

For his overall impression of Puget Sound, Brian says the waterway is generally clean and fairly intact, although the amount of shoreline occupied by concrete, rock and wooden bulkheads is fairly extensive.

“There are some plastic bottles here and there, and we pick up garbage when we can,” he said. “I saw many places where people were just enjoying the beach. From a spiritual standpoint, experiencing the beauty, the Salish Sea is an incredible place.”

Brian recalls a memorable event that occurred while motoring around the south side of Lopez Island in North Puget Sound as a dense fog bank rolled in and visibility dropped to nearly zero.

“You could hear sea lions snorting,” he said, relating how he he stopped his skiff out of concern for submerged hazards. “All of a sudden, right next to me, I heard the sound of a whale surfacing. But the fog was too thick to see it.”

Once, Brian and Rob even had the chance to save a human life as darkness fell upon the cold waters of Puget Sound.

“We were just south of Blaine (near the Canadian border). I picked Rob up and we were heading out of a little bay with the kayak on the skiff. I heard a faint sound like a bird. I had never heard a bird like that.

“I shut off the motor and could hear a faint voice in the distance yelling ‘help.’ I looked off to starboard and 300 meters away there was a sailboat. A couple hundred meters away, I saw something bobbing on the water. A guy in his 70s had gotten knocked off his sailboat and his life vest had inflated so much that it was keeping his arms up in the air.”

“We were able to get to him and get him back on his boat,” Brian said. “It was a most extraordinary thing.”

The man was floating all alone in currents that would have taken him into Canada, Brian said. Given the conditions, it appears likely that he would have died without help.

Brian says the shoreline mapping project provides a good chance for people of the region to understand the dimensions and conditions of the Puget Sound shoreline simply by going online. The more that people can see and understand shoreline habitat, the more they will try to protect it, he said, adding that helping to create this unique public access has given his life a greater purpose.

A final report, released in March, summarizes the first Soundwide survey:

“The Puget Sound Shoreline Mapping Project reflects what is possible when technology, coordination, and mission-driven fieldwork come together to address complex environmental challenges… This effort lays the groundwork for more informed and equitable conservation, restoration, and shoreline planning. As the project continues into its next phase, it offers a model not only for Puget Sound, but for other coastal regions seeking scalable, data-driven approaches to protecting their shorelines.”

comment:

All imagery is geotagged and time-stamped, producing seamless “virtual tours” accessible via the EarthViews platform

Scalable model: This “on-the-water street view” can be expanded to other sensitive coastal regions, supporting comparative ecological studies and long-term monitoring worldwide.

This innovative blend of paddling, panoramic imaging, and mapping transforms how we visualize and study shorelines.

It bridges the gap between aerial surveys and ground-level inspection — making detailed, nearshore habitat information accessible, repeatable, and scalable. For ecological monitoring, shoreline resilience, and public engagement, it offers a powerful new tool—poised to enhance restoration efforts, inform coastal policy, and foster more inclusive stewardship of marine environments.