I recently completed a much-involved writing project focused on environmental justice. It has been one of the most challenging, yet for me enlightening, efforts in my 45 years of covering the environment.

My initial idea was to report on a plan by the Washington Department of Ecology to rewrite the regulations for the Model Toxics Control Act, the law that prescribes the cleanup of all kinds of contaminated sites. One of Ecology’s goals in rewriting the rules has been to pay more attention to the demographic makeup of populations around polluted sites, making sure that families of color, low-income and other highly impacted groups are given the attention they deserve.

I naively approached this story as I would any story regarding potential changes to public policy. Regulations often revolve around agency activities with input from community activists, guided by science and influenced by political leaders. I am fairly comfortable dealing with political leaders and scientific discoveries in the fields of biology, chemistry, oceanography and such. But I had never been trained in sociology, which is at the heart of environmental justice. I found myself questioning basic ideas, searching for reliable studies, wondering about methodologies, and relishing personal revelations about race, class, political power and history.

I started by digging for answers: Is it really true that toxic sites are more often found in disadvantaged communities? How did this come about? Why are toxic-cleanup efforts more often focused on affluent areas? What are the social forces that led to today’s circumstances? What are the forces for change versus those for maintaining the status quo?

I can’t say that I found all the answers, and I’m still learning. I plan to write more about environmental justice in the future, as more people realize that our efforts to treat the environment with greater respect also means treating all people with greater respect. For now, I’ve written three stories, all published this week in the Encyclopedia of Puget Sound:

- Revised toxic-cleanup rules will increase focus on environmental justice

- Diverse populations benefit from targeted efforts to improve environmental justice (Duwamish Valley)

- Why is so much pollution found in disadvantaged communities?

When it comes to political struggles, there is increasing awareness about the need to address environmental justice. Lots of things are happening at the state and federal levels. Washington’s Legislature is moving ahead with a bill that would require state agencies to establish new EJ practices when dealing with health and environmental issues. Senate Bill 5141 has passed both houses in somewhat different forms and is now going through reconciliation before final passage.

At the national level, President Joe Biden has launched a new White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council to bring greater visibility to EJ issues and to make sure that federal agencies remain committed to more equitable outcomes for a variety of environmental and climate issues.

When it comes to Washington state, it is clear that more studies are needed to assess the geographic and demographic distribution of toxic sites. Statewide studies seem to be either out of date or limited in other ways. Few, if any, have been peer-reviewed for credibility. Still, some localized studies point to an inequitable distribution of toxic sites, thus supporting the findings of well-researched studies in other parts of the country. It is time to understand that low-income communities and communities of color are not only affected disproportionately by the location of toxic sites but also that their homes, healthcare services and working conditions may put their health at greater-than-average risk.

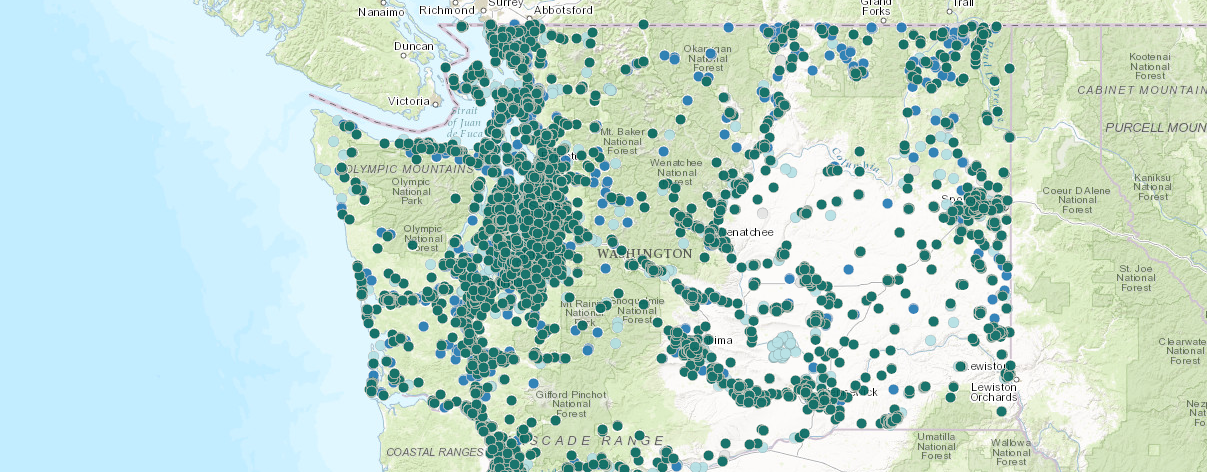

One useful demographic tool that anyone can use is the Washington Environmental Health Disparities Map, which compares conditions across the state, grouped by census tract. The map looks at 19 indicators — including proximity to Superfund sites, exposure to diesel emissions, and toxic releases from industrial facilities. It also includes comparative data on poverty, race, housing costs and English proficiency, among other things. You can type in your address and learn how your area compares to other areas across the state.

Displaying all this information by census tract creates some limitations, because census tracts vary greatly in size across the state. Nevertheless, it is a nice high-level snapshot of these conditions, and the “Information By Location” tool provides a good starting point to see how your “community” compares to others in the state. An explanatory video offers information about using the map, which was developed by the University of Washington’s Department of Environmental and Health Sciences in collaboration with Front and Centered, a nonprofit group, the Washington departments of Health and Ecology, and the Puget Sound Clean Air Agency. The project is more fully explained in a report (PDF 10.9 mb) from the Washington Environmental Justice Mapping Work Group.

As I continued my exploration of EJ issues, I felt compelled to seek out answers about why certain “vulnerable” populations were getting more than their fair share of environmental hazards. On the one hand, I told myself that regardless of the history we must deal with things as they are today. On the other hand, the conditions of today are derived from the conditions of yesterday, as explained by Millie Piazza, environmental justice senior adviser for the Washington Department of Ecology.

“We have to realize that history is important in order to deal with the problems of today,” Millie told me. “If we keep supporting systems that led to these problems (of racial and economic injustice), then we will keep getting the same results.”

My story “Why is so much pollution found in disadvantaged communities?” provides a general answer to my initial question, although the history of industrialization and the resulting pollution is different for each community across the state and nation.

For a more thorough explanation of the history of racial and income disparity as they relate to environmental justice, I can recommend two excellent books: “Toxic Communities: Environmental Racism, Industrial Pollution, and Residential Mobility” by Dorceta Taylor; and “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America” by Richard Rothstein.

To see how environmental justice played out in one community, I examined the history of the Duwamish Valley in South Seattle, where a pristine river was converted to an industrial waterway. Check out my story “Diverse populations benefit from targeted efforts to improve environmental justice.” I’m grateful for help from BJ Cummings, author of “The River That Made Seattle: A Human and Natural History of the Duwamish.”

I’m currently looking into a few other communities where the injustice of pollution seems to maintain a stranglehold on area residents, who find themselves stymied in their efforts to reduce unhealthful conditions.

I have learned by diving into this issue of environmental justice that we are all affected in widely differing ways by our environment, and we all have the power to make changes to our environment, for better or worse. The essence of environmental justice is to include everyone and forget no one in our choices for change.

While I can never understand what it means to be a person of color or to live in poverty, I am learning a good deal from people who have other life experiences. As a result of new efforts at the local, state and federal levels, I see hope for a better future.

Mr. Dunagan, I was greatly impressed with your recent Model Toxics Control artcle and now with your diving even more wholeheartedly into the issues. I volunteered for the Duwamish River and other watersheds years ago and for the last 20 have struggled to help defend affected habitat and earthlings around Bellingham Bay. Thank you for your comprehensive, clear, prodigious coverage of important topics.

Thank you for taking time to write. I appreciate your efforts to protect the environment and people.