The year 2025 has been fairly mystifying to experts who make their living studying natural systems in the Puget Sound region.

Unusual observations this year include record-low dissolved oxygen levels, unexpected gray whale visitations, and the sudden arrival of an astounding number of short-tailed shearwaters — a seabird almost never seen in Puget Sound.

Cold waters rising from the deep along the West Coast helped to rescue Puget Sound from an oceanic heat wave bringing warm-water troubles to other parts of the Pacific Ocean. But our inland waterway has had its own problems, and the reasons have been a challenge to explain.

As they say, all things in nature are connected. Lately, it seems the connections themselves are changing — or at least harder to understand. That has led to calls for new studies and more involved scientific explanations. All the while, the lack of explanations has not dulled the enthusiasm of local observers driven by a deep respect for the natural world.

Shearwaters hold a surprise party

It was mid-October when bird expert Peter Hodum launched his kayak at Owen Beach in Tacoma’s Point Defiance Park. Hodum had heard that thousands of short-tailed shearwaters had appeared suddenly in Northern Puget Sound, to the amazement and delight of bird watchers throughout the region.

“I had seen short-tailed shearwaters from a distance in groups of three or four,” said Hodum, a professor in conservation biology at the University of Puget Sound. The chance to see dozens or even hundreds at once was something he did not want to miss.

“It was a gorgeous sunny morning when I paddled out into the channel,” Hodum recalled.

About 100 of the shearwaters were soaring on a light breeze across Dalco Passage. Some were floating on the water. One bird crossed his path, left to right, just off the bow of his kayak.

“It came within 10 or 15 feet,” he said. “I could practically touch it with my paddle. I still have this vivid image of a bird with a beautiful glint in its eye, illuminated by the sun.”

Hodum grew up in New Jersey, attending Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine. It was there that he acquired a lifelong love of seabirds, particularly the storm petrels, he said. This ocean-skimming seabird got its name from seafarers who observed them flying alongside ships during storms. Like the short-tailed shearwaters, storm petrels spend their time almost entirely out at sea, well offshore.

Hodum’s interest in seabirds took him to the University of California, Davis, where he completed his PhD in ecology with a specialty in conservation biology. His ongoing research and teaching career have generally focused on conservation, always with an eye on seabirds. In 2004, he moved to the Puget Sound region and a year later began teaching at UPS.

An avid kayaker, Hodum gets out on the water as often as he can.

“I love being out on the ocean,” he said. “You are sitting at water level, moving through it and feeling so connected. It’s a wonderful way to exist in the natural world.”

His “particular weakness” for petrels and shearwaters goes well beyond their remarkable lives in the open ocean, where they soar upon the wind, swoop down to catch their food and even dive beneath the waves. These birds, he says, are simply the epitome of grace. Nothing compares to them.

“Given how these birds resonate so deeply with me in an emotional and aesthetic way, it was particularly magical to see them on the water within a couple miles of my house.”

And yet a sense of apprehension somewhat clouds his joy, as Hodum faces the fact that these short-tailed shearwaters seem to be out of place in Puget Sound, where observers reported 1,800 near Tacoma, 2,300 near Anacortes and 1,100 near Port Townsend, with some birds counted more than once, according to the bird-watching site eBird.

Hodum said this sentiment aligns with a feeling last spring when mild, sunny weather came early and lingered. “Isn’t this lovely, but it should be raining,” he explained.

In the same sense, “These birds near my home are hundreds of kilometers from where they should be,” he added.

Reasons for the short-tailed shearwaters visiting Puget Sound might well be connected to a variety of unusual phenomena, with likely connections to weather, ocean conditions and long-term climate warming.

Children of “the blob”

“The blob,” a massive heatwave that occurred from 2014 to 2016, has become infamous for its devastating effects on the ecosystem in the Pacific Ocean and along the coasts. Water temperatures at the time were reported as high as 7 degrees C (12 degrees F) above normal in a few places, with an exceedance of 4 degrees C in many places, including parts of Puget Sound.

The blob’s high-temperature and low-nutrient waters disrupted the food web, killing an estimated 1 million to 4 million seabirds, particularly common murres and Cassin’s auklets. Sea lions, sea otters and whales were found dead along the coast. Warm-water species appeared to move northward into normally cooler waters, altering the available food supply. And disease became a known factor for many species, including the sunflower sea star, a keystone species that, in time, was practically wiped out along the West Coast.

In terms of death and disruption, nothing like the blob has been seen since, but each of the last six years has been marked by unique heat waves creating their own problems, and this year’s warm ocean conditions have caught the attention of many experts. The altered migration pattern of the short-tailed shearwaters along with increased deaths of gray whales are just two of the anomalies that could be related to the ecological effects of warm waters in the far north, experts say.

The recent heat wave, which began in May, waxed and waned erratically, with high surface-water temperatures covering most of the North Pacific by August. Designated NEP25A (with “NEP” standing for Northeast Pacific), the heat wave’s warm waters were sitting right off the West Coast by September — up to 3 degrees C (5.4 degrees F) higher than normal off Washington and elevated by up to 4 degrees C (7.2 degrees F) off California.

Some observers anticipated a major influx of this warm water into Puget Sound, with potentially devastating consequences, such as occurred in 2014, when conditions allowed warm water to rush in during September, raising the temperature of the Sound up to 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F) within two weeks. But this year there was no repeat performance. The difference appears to be a nearly steady and ongoing upwelling of deep, cold seawater along the coast. The upwelling, driven by winds out of the north, displaced and cooled the warmer incoming water, said Nick Bond, a longtime climatologist who first designated the 2014-16 heat wave as “the blob.”

In late September this year, the winds shifted, resulting in a brief downwelling, somewhat on the normal schedule. But then the upwelling resumed and generally continued until late October. By the time the seasonal, more frequent downwelling began in mid-October, surface temperatures in the ocean had returned to near-normal levels, thanks to cooler, windier weather. It seems that Puget Sound escaped the higher temperatures this time around, although the waterway still remains above the historical average temperature.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, this year’s heat wave will go down in the record books as the largest in size across the North Pacific, with higher temperatures than ever before. Warm water covered some 4 million square miles at its maximum, based on temperatures measured at the ocean’s surface.

“But sea surface temperatures don’t tell the whole story,” Bond said, noting that maps of this year’s marine heat wave showed it dissipating rather quickly in the Northeast Pacific Ocean, in part because the warm waters did not go very deep. In contrast, the blob of 2014 persisted because the warm waters created a moving mass of higher-temperature water that continued into the next year. For the past few years, a deep pool of warm water has been hanging off the Asian coast, reaching out to the middle of the North Pacific, where it could continue to play a role in ongoing heat waves as well as affecting weather in North America, Bond said.

Thanks to underwater drones operated by NOAA, such changes in water conditions are somewhat easier to track these days, he said, but putting the information together and using it to predict effects on the food web remain a major challenge.

“We should be expecting reorganizations in the marine food web,” he said. “The variability in the climate brings changes in the community structure, so it makes sense that there will be winners and losers. There will also be surprises — some happy surprises and some unhappy surprises.”

What happened with the birds?

While the 2025 marine heat wave was raging in the North Pacific, high temperatures were being measured up into the Gulf of Alaska and even into the Chukchi and Beaufort seas in the Arctic Ocean — all places where short-tailed shearwaters are known to spend their summers looking for food.

When one considers that these birds travel some 9,000 miles each year from their breeding grounds near Australia to reach their summer feeding grounds up north, it is no wonder that bird enthusiasts are awe-struck by their resilience. The birds generally make that trip in 10 to 15 days.

“Short-tailed shearwaters are absolutely incredible,” said Charlie Wright, who helps track seabird mortality for COASST, the Coastal Observation and Seabird Survey Team. “They have evolved their own strategies for how to exploit the waters around Alaska for food.”

Unfortunately, he said, summer heat waves up north have been playing havoc with their food supply, which includes shrimp-like crustaceans such as tiny krill and copepods. A new assessment of Arctic heatwaves by an international group of researchers shows a dramatic alteration in the food web, including a reduced size and fat content of the prey available to birds like the shearwaters.

Why the short-tailed shearwaters came to Puget Sound in large numbers may well be traced to their struggle to find enough nutritious food in their normal feeding grounds, according to speculation by several bird experts interviewed for this story. All were surprised that so many birds would take a detour into Puget Sound, most apparently coming through the protected coastal waters east of Vancouver Island, sometimes called the Inside Passage.

“We were all gobsmacked by this event,” said Wright, who also serves as a volunteer reviewer of data submitted to eBird, a website that compiles bird-sighting information. “It was nothing like anything we have ever seen.”

While the deaths of marine birds have become associated with marine heat waves, the short-tailed shearwaters might survive hard times by looking for new places to forage, as suggested in a research paper by a group of Australian scientists. Perhaps this year the shearwaters were not in dire straits but were just running low on energy, so they dropped in to refuel.

Wright says a shift in their migration pattern was first noted in 2021, when 2,000 short-tailed shearwaters showed up at the north end of Vancouver Island to the surprise and delight of bird enthusiasts who had never seen them there before. Other areas of British Columbia also saw increased numbers that year, as described in a report. Since then, the numbers have increased. This year, some 7,800 short-tailed shearwaters were spotted near the south end of Vancouver Island by the group Rocky Point Bird Observatory, which reported a similar number last year.

As for Puget Sound, the number of short-tailed shearwater sightings dwindled from mid-October to mid-November, when the last ones were reported in the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

“We were all following this event in real time,” Wright said. “Now we are waiting for the fall of 2026. Will what happened this year become a new normal?”

Gray whales struggling to survive

Warming waters off Alaska in recent years appear to be taking a major toll on gray whales along the West Coast, most of whom undertake one of the longest annual migrations of any mammal. Each fall, they travel some 6,000 miles from feeding grounds in Arctic and sub-Arctic waters south to breeding grounds in Baja California, before returning north in the spring.

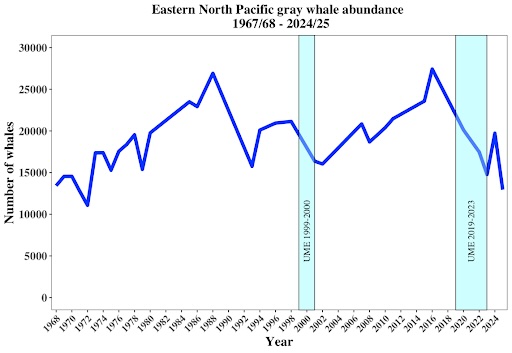

After decades of ups and downs, the population of Eastern North Pacific gray whales has been in a steep decline for the past 10 years, dropping to about 13,000 animals this year — less than half the 27,000 estimated for 2016. This is the smallest number since 1972 — the year the Marine Mammal Protection Act was adopted by Congress.

For a variety of species, warming water favors the growth of less desirable prey over more nutritious choices. For gray whales, there is an additional effect that impairs their ability to get enough food. Warmer waters mean less sea ice, which supports the growth of algae that live on the underside of the ice, as described in a 2023 article in the journal Science. These algae die and sink to the bottom, where they feed the benthic (bottom-dwelling) organisms, particularly shrimplike amphipods. Gray whale anatomy is uniquely adapted for scooping out and filtering sediments on the bottom.

Less sea ice caused by longtime warming, not just marine heat waves, means less algae and fewer benthic critters, to the detriment of the whales. In addition, more open water leads to stronger currents, which can wash away the fine sediments required by some nutrient-rich amphipods.

While melting ice and open seas may offer new feeding areas for the whales to explore, the overall benthic abundance may be inhibited.

“Poleward shifts in gray whale feeding locations have already been documented, which likely reflect the declining quality and shifting distribution of their preferred prey,” the article states. “Future declines in benthic biomass will likely drive decreases in gray whale carrying capacity that cannot be offset by continued increases in ice access.”

John Calambokidis, a whale researcher with Cascadia Research Collective in Olympia and an author of the report, said gray whales in the Arctic have already begun targeting prey not found on the bottom, such as krill and herring roe.

“These whales are remarkably resilient,” he said, “but clearly they are built for feeding on the bottom.” So far, it seems that changes in their prey selection have not been able to avoid population declines during tough times in the Arctic.

Interestingly, two subgroups of these gray whales seem to be holding their own by adopting different migration patterns. One is a group that takes a detour into Puget Sound during the spring migration north when they are most vulnerable. Nicknamed “the sounders,” they seek out a specific location near Whidbey and Camano islands.

“The sounders part of the gray whale story is a positive one,” Calambokidis said. “The sounders have seen increases in number each time there is a major mortality event.”

Apparently, in desperation for food, a few newcomers in the gray whale population occasionally join the long-term sounders that have been stopping by for many years. Feeding on ghost shrimp buried in Puget Sound sediments is a “high-risk feeding strategy,” Calambokidis said, because the whales must enter shallow water at high tide and risk getting stuck when the tide goes out. Yet the strategy has paid off time and again.

“These whales have had a remarkable survival, in part because they found this rich food source,” he said, adding that three of the six whales first seen in 1991 are still coming back, and the numbers are increasing. Today, there may be as many as 20.

While the sounders typically show up during the spring migration north, five showed up last December and into January, foregoing the rest of the trip to breeding and nursery grounds in Baja California, where mating takes place and calves are born. It turned out to be an unusually poor reproductive year — the lowest on record — with an estimated 84 births. That compares to a previous 10-year average around 730.

Perhaps lacking normal fat reserves, the whales that chose to stay in Puget Sound took advantage of the local ghost shrimp while avoiding the energy-depleting trip farther south.

Another notable faction within the gray whale population is the Pacific Coast feeding group, some 250 whales that travel from the southern breeding grounds to West Coast areas from California to British Columbia. These animals tend to be smaller in size, perhaps because they do not partake of the Arctic feast. Their numbers remain stable or in a slight decline, unlike the wild fluctuations of the larger population.

In several feeding areas along the coast, the whales consume swarms of mysid shrimp swimming near the surface and in kelp beds. Warmer water, particularly during marine heat waves, can affect the survival and reproduction of mysids directly as well as altering their habitat, including kelp. Given the uncertainties in ocean conditions, the future remains uncertain for this unique group of gray whales.

These ideas are explored briefly in a new journal article, “What gray whales are telling us about ecosystem change in the Pacific Arctic,” written by marine mammal biologists, including Calambokidis.

Unusual water conditions in Puget Sound

While cold-water upwelling this fall kept the marine heat wave at bay, the deep, nutrient-rich water coming into the Strait of Juan de Fuca from the ocean was not only cold but also low in dissolved oxygen.

University of Washington oceanographer Jan Newton reported especially low hypoxic waters (below 2 milligrams per liter) in deep water at the south end of San Juan Island during a UW student research cruise in October.

“That was something never seen (at that location) over the past 20 years of observations,” she said.

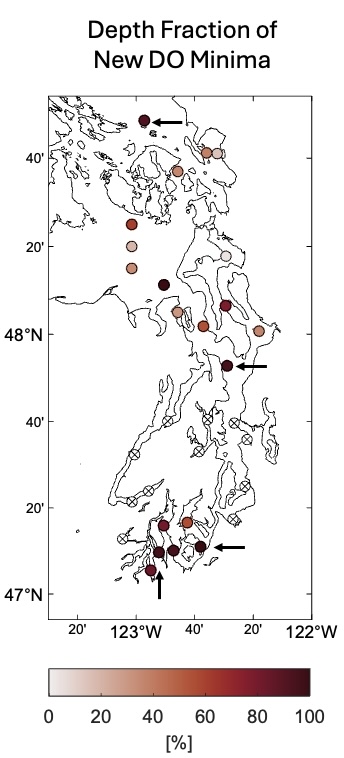

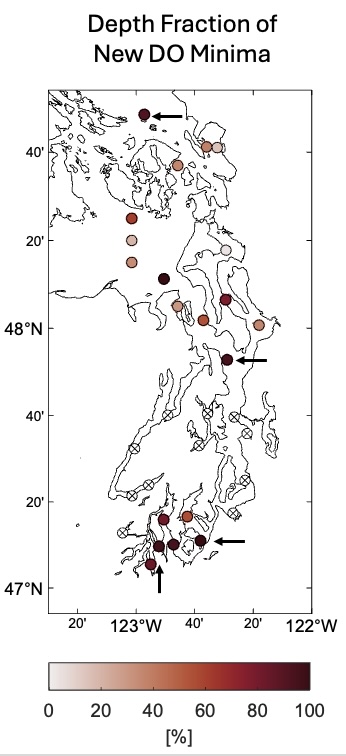

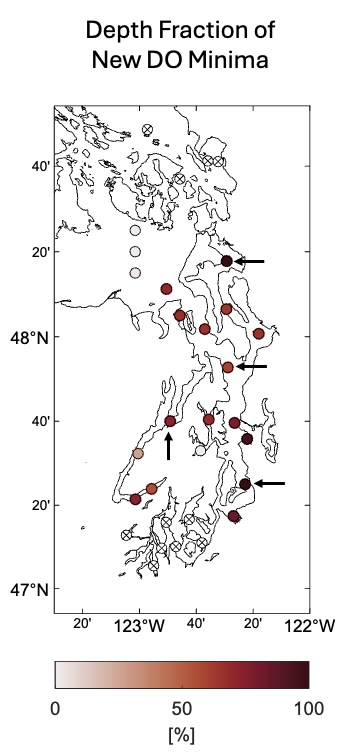

Record-low oxygen levels also were reported in several locations throughout Puget Sound not known for being low-oxygen areas, said Natalie Coleman, ocean acidification scientist with Washington Department of Ecology. Measurements were taken from the water’s surface down to the bottom once a month. A few areas showed record lows throughout the water column, as shown on maps on this page. Others showed records at various depths. Most of these areas never reached the dangerous lows of hypoxia, however. Records in this case go back to 1999.

Southern Hood Canal, which is known for low oxygen in the fall, also broke records for low oxygen at mid-depth this year. While bottom waters reached hypoxic conditions in the extreme south, no fish kills were reported, probably because the low-oxygen layer never reached the surface.

Low-oxygen levels are often explained by describing the boom and bust of plankton falling to the bottom and being degraded by bacteria, which consume the available oxygen. In Puget Sound, the main driver is nitrogen from natural and human sources. But low oxygen levels in early spring can’t be explained entirely by this biological process, which takes time to develop, Coleman said.

Besides the low-oxygen waters pushing in from the ocean, other factors in recent years involve low rainfall and limited snowpack, which decrease river flows and reduce circulation and mixing in Puget Sound. Less freshwater coming into Puget Sound tends to decrease estuarine flow — often described as a “conveyer belt” with lighter freshwater flowing out of Puget Sound at the surface, causing heavier seawater to come in at the bottom. Slower flows mean less mixing and declines in dissolved oxygen.

Lower freshwater inflows also result in warmer, saltier seawater, which cannot hold as much oxygen.

“This has been yet another year of very low flows, which is one component of why we are seeing DO minima,” Coleman said.

Another unusual condition this year in Central Puget Sound was the lack of a persistent bloom of phytoplankton, tiny organisms that contain chlorophyll, according to Kim Stark, a marine biologist for King County.

“This year and last year, there seemed to be plenty of nutrients around,” she said, but they weren’t being taken up by the phytoplankton, as determined by measuring the level of chlorophyll.

“Usually, light is not a limiting factor after spring,” she noted.

The layering of lower inflows of freshwater should have encouraged plankton growth, she said, but it didn’t do that for much of Central Puget Sound this year.

“For at least 10 years, I’ve been looking at this type of data, and I have never seen anything so puzzling,” said Stark. Such results might be explained if the two-week sampling frequency somehow missed a plankton bloom, she added, “but I don’t think that is the case.”

The northern portion of Central Puget Sound typically has a strong phytoplankton bloom in the fall, but that didn’t take place this year. Equally strange was that Seattle’s Elliott Bay, which normally has low phytoplankton growth because of turbid water, had some of the highest levels this year.

“Here we are having this low biomass year — except for the one place we expect it to be low,” she said. “It is going to take some sleuthing to figure it out.”

Phytoplankton typically feed a huge assortment of zooplankton, including many tiny animals and the young larvae of fish and invertebrates. The total number of zooplankton in the northern part of Central Puget Sound was lower than normal this year, according to Karen Chan, a UW zooplankton ecologist, but the biomass there was somewhat average. In the southern part of Central Puget Sound, biomass was slightly higher.

“These trends suggest a change in species composition,” she noted.

Effects on the food web of different plankton species are hard to predict, said Chan, but an observed increase in planktonic larvae this year might mean that warmer conditions resulted in an earlier reproductive peak among invertebrates.

One issue that concerns scientists is that an early growth of certain larval species can create a mismatch in timing within the food web, Chan said. If larvae are released too early, phytoplankton may not yet be available for them to consume. Also, early-released larvae might grow enough to be mismatched with young fish and other predators that need a particular size of food. Water temperature and currents can affect the survival and growth of these tiny creatures integral to the marine food web.

Much of the physical and biological data from this year’s anomalies in Puget Sound are still being analyzed by scientists, many of whom get together each April to compare notes and attempt, in a small way, to piece together the big puzzle of Puget Sound.

UW oceanographer Jan Newton said researchers throughout Puget Sound are gathering information and finding meaning for their own piece of the puzzle, but nobody has been assigned the task of looking at the big picture.

Lots of money goes out for restoration, and some is directed to measuring changes to parts of the ecosystem, she said, but what is needed is one or more people in the region to seek out and find the connections.

“We have people studying components of the ecosystem,” she added, “but nobody has the job of looking across the whole system.”