UPDATE: July 23

The Great American Outdoors Act passed the House yesterday on a 310-107 vote. See Associated Press and news release from U.S. Rep. Derek Kilmer, D-Gig Harbor.

—–

It appears that the political stars are lining up for what some people are calling the most significant environmental legislation in decades. Billions of dollars have been laid upon the table for parks, recreation facilities and environmentally sensitive lands across the country.

The U.S. Senate has already passed the Great American Outdoors Act, which pairs two previous spending proposals: the Land and Water Conservation Fund with $900 million to be spent annually for the foreseeable future, and a new National Parks and Public Lands Legacy Fund with $9.5 billion to be spent over the next five years.

The House is poised to approve the measure when it returns to full session July 20, despite a last-minute effort by one Republican lawmaker to amend the bill. If successful, that could delay action for another year or more.

President Trump, who has consistently pushed for major funding cuts for conservation — including the Land and Water Conservation Fund — suddenly reversed course in March. Now he says he will enthusiastically sign the funding bill.

Trump’s Interior Secretary, David Bernhardt, expressed the administration’s support. “The enactment of the combination of these two proposals,” he said in an opinion piece, “would be the most significant conservation legislation in generations.”

On that point, he hasn’t gotten much argument from conservation groups.

“This is an historic deal reflecting the tremendous bipartisan support for our public lands and would mark the biggest conservation victory in over 100 years,” said Tom Cors of The Nature Conservancy, a spokesman for the Land and Water Conservation Fund Coalition.

Kabir Green, director of federal affairs at the Natural Resources Defense Council also agreed. “At a time when the outdoors is more important to public health than ever, a bipartisan majority is recognizing how badly the country needs to invest in its public lands and waters and ensure access to them.”

Their comments and many others were compiled by the Senate Republican Communications Center.

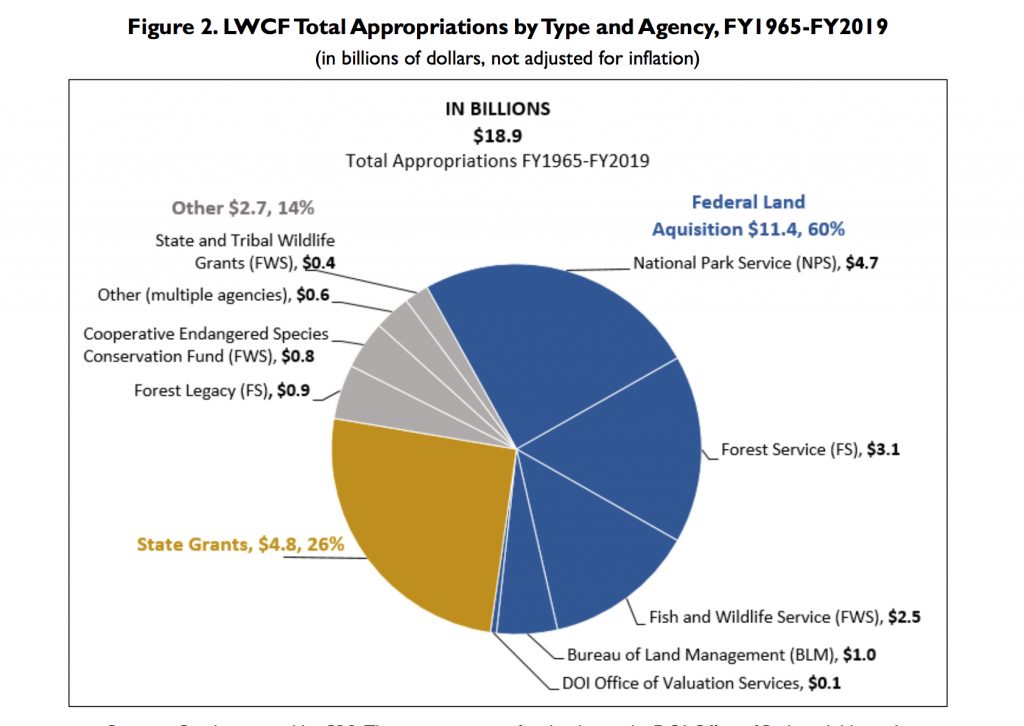

The Land and Water Conservation Fund has been on the books since 1964, providing nearly $19 billion for conservation projects across the country. The fund was first proposed by a federal commission, supported by President John F. Kennedy and ushered through Congress by Sen. Henry M. Jackson of Washington state, who chaired the Senate Interior Committee at the time.

Congress first authorized the fund for 25 years, then approved a 25-year extension. In recent years, however, political squabbling allowed the fund to expire twice: once in 2015, when it was revived for three years, and again in 2018, when its annual authorization of $900 million was made permanent.

Even so, perpetual authorization does not mean that Congress must spend the money.

That’s why the new Great American Outdoors Act is so significant, said Amy Lindholm, manager of the LWCF Coalition. In addition to the new funding piece to help eliminate a $12-billion maintenance backlog in national parks, the new legislation actually mandates that at least $900 million be spent each year for land purchases and recreation projects.

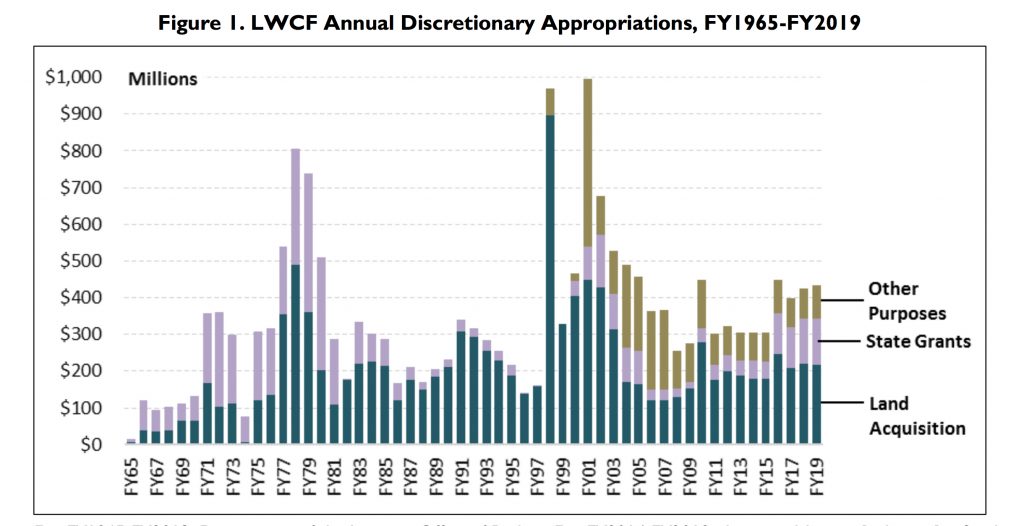

That mandate will make a real difference, Amy told me. Even though Congress has authorized spending at the $900-million level since 1978, it has spent less than half that amount. If the fund were a bank account — which it isn’t — it would contain a balance of about $22 billion, compared to withdrawals and spending of $18.9 billion through the years. Once the new law is enacted, it would take an act of Congress to stop the flow of money.

Spending targets: LWCF

The Land and Water Conservation Fund derives its $900 million in annual credits mostly from federal royalties for offshore oil and gas drilling, which have generated a total of about $7 billion a year for the U.S. government in recent times.

Money in the LWCF goes for three major purposes:

- Land acquisition and outdoor recreation programs in the Forest Service, National Park Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, and Bureau of Land Management.

- Financial assistance to the states for recreational planning, acquisition of recreational lands and waters, and developing outdoor recreational facilities. States receiving funds must provide an equal amount of money.

- Other federal resource-related purposes, including the Forest Legacy Program of the Forest Service, which helps states to acquire important lands, and the Cooperative Endangered Species Conservation Fund of the Fish and Wildlife Service, which helps states to protect listed species.

In Washington state, two federal projects are riding high on the list for funding in the next budget: the Willapa National Wildlife Refuge and the Dewatto Headwaters Forest. Many grants to state agencies have been proposed but not yet been prioritized.

Spending targets: National Parks

The National Parks and Public Lands Legacy Fund would direct up to $9.5 billion in revenues from on-shore, off-shore and renewable energy supplies to the following:

- National Parks, 70 percent

- U.S. Forest Service, 15 percent

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 5 percent

- Bureau of Land Management, 5 percent

- Bureau of Indian Education, 5 percent

Deferred maintenance in the national parks alone is estimated at $12 billion. The National Park Service would use its share of the fund to repair roads, buildings, campgrounds, trails, utility systems and other infrastructure.

National parks in Washington state are facing a backlog of more than $427 million in needed repairs, according to a report by Pew Charitable Trusts (PDF 223 kb). That includes $186 million at Mount Rainier and $126 million at Olympic.

History of LWCF

The Land and Water Conservation Fund was created during the heyday of the environmental movement during the 1960s, when Sen. Henry M. “Scoop” Jackson played an instrumental role as chairman of the Senate Interior Committee. Legislation during his tenure included the Wilderness Act, creation of North Cascades National Park, National Trail System Act, Wild and Scenic Rivers Act and, perhaps most significant, the National Environmental Policy Act.

As the Senate prepared to vote on the LWCF for the first time, Jackson spoke to his fellow senators:

“I would like to remind you that it is mostly to the open areas that 90 percent of all Americans go each year, seeking refreshment of body and spirit,” he said. “These are the places they go to hunt, fish, camp, picnic, swim, for boating or driving for pleasure, or perhaps simply for relaxation or solitude.”

The vote was 92-1.

The original funding came from the sale of federal property ($50 million a year), motor boat fuel tax ($30 million), new entrance and user fees ($65 million) and $60 million over eight years to be paid back to the treasury. The new user fees never raised more than $16 million, so the oil and gas revenues were added in 1968 and soon became the major source of funding.

Authorized spending was increased to $200 million a year in 1968, then to $300 million in 1970, and then to $900 million in 1977 — although spending reached that annual level only twice (see chart).

Jackson’s successors who occupied that same Senate seat — Dan Evans, Slade Gorton and Maria Cantwell — have all been supporters of the LWCF, with Cantwell working especially hard in recent years to strengthen the law.

“Public lands are a great driver of our economy and an essential aspect of American life, and this vote says we’re going to continue to invest in them,” Cantwell said in a news release after the Senate approved the Great American Outdoors Act on a 73-25 vote. “It couldn’t be a more important investment, and it couldn’t give America a bigger return.” (Check out her speech on video, this page.)

Today’s politics

Until this year, President Trump showed little interest in acquiring more federal lands or creating new recreation areas. Congress consistently overruled his proposed budgets to gut the funding for the LWCF.

On March 3, Trump appeared to change his tune with this tweet: “I am calling on Congress to send me a bill that fully and permanently funds the LWCF and restores our national parks. When I sign it into law, it will be HISTORIC for our beautiful public lands. All thanks to @SenCoryGardner and @SteveDaines, two GREAT conservative leaders!”

Some have speculated that Trump’s change of heart is designed to improve the election prospects of the named Republican senators, Cory Gardner of Colorado and Steve Daines of Montana, but Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell insists it was not a political move.

“It’s in proximity to the election, but nobody said you ought to quit doing things just because there’s an election,” McConnell was quoted as saying in “The Hill.”

Given Trump’s sign-on and with supportive Democrats in control of the House, the chances of approving the long-term funding appear good. But that hasn’t stopped Utah Sen. Rob Bishop, a Republican, from raising alarms about a confusing provision in the bill that would remove restrictions about where the money can be spent for land purchases. Reporter Emma Dumain describes the situation in E&E News.

“Eastern states deserve equality in federal land ownership as Congress intended,” Bishop wrote in a letter to 154 House members. “A last-minute ‘conforming amendment’ … eliminated this requirement, siphoning critical LWCF funds away from Eastern states in perpetuity. It’s not right.”

Stepping into the fray, a spokeswoman for Republican Sen. Daines played down the controversy.

“The conforming amendment makes no change to the status quo,” Katie Schoettler was quoted as saying in the E&E News article. “Congress and the agency have consistently approved and funded Western LWCF projects to meet needs and fulfill congressional intent behind the program. Eliminating this arbitrary cap just ensures LWCF is carried out as it always has been.”

If Bishop can dredge up enough votes to pass his amendment, all sorts of trouble could follow, and the bill would need a new vote in the Senate — which might not happen soon. Most House Democrats are expected to stay away from that “Pandora’s box,” as writer Dumain describes it, but in recent years turmoil has never been far from the Land and Water Conservation Fund.

Further reading

- Congressional Research Service: “Land and Water Conservation Fund: Overview, Funding History, and Issues” (PDF 1.2 mb)

- Congressional Research Service: “Land and Water Conservation Fund: Frequently Asked Questions” (PDF 355 kb)

- Pew Charitable Trusts: National park case studies

- Pew Charitable Trusts: Olympic National Park fact sheet

- Watching Our Water Ways: “Federal Land and Water Conservation Fund gets tangled in politics.”

- Anniversary publication: “Land and Water Conservation Fund: 50 years in Washington” (PDF 3 mb) by Ethan Fetz, Washington Wildlife and Recreation Coalition, with Hannah Clark and Frances Dinger.

No Comments yet!