When considering the amazing migration of salmon, we often talk about their long journey from the ocean, guided by smell, to the very stream where they first emerged from the gravel.

But if we’re talking about salmon recovery — such as avoiding extinction for Puget Sound Chinook — we must focus equally on the first leg of their journey — from stream to ocean. That’s when vulnerable young fish die by the millions.

The survival rate for juvenile salmon depends to a large extent on the physical condition of the shoreline, which is why I became interested in writing about the Seattle seawall. Check out “New Seattle seawall improves migratory pathway for young salmon.”

I also wrote about a proposal to expand the goal of “no net loss” of shoreline function to one of “net ecological gain.” I’ll review the historical context of that idea in the second half of this blog post.

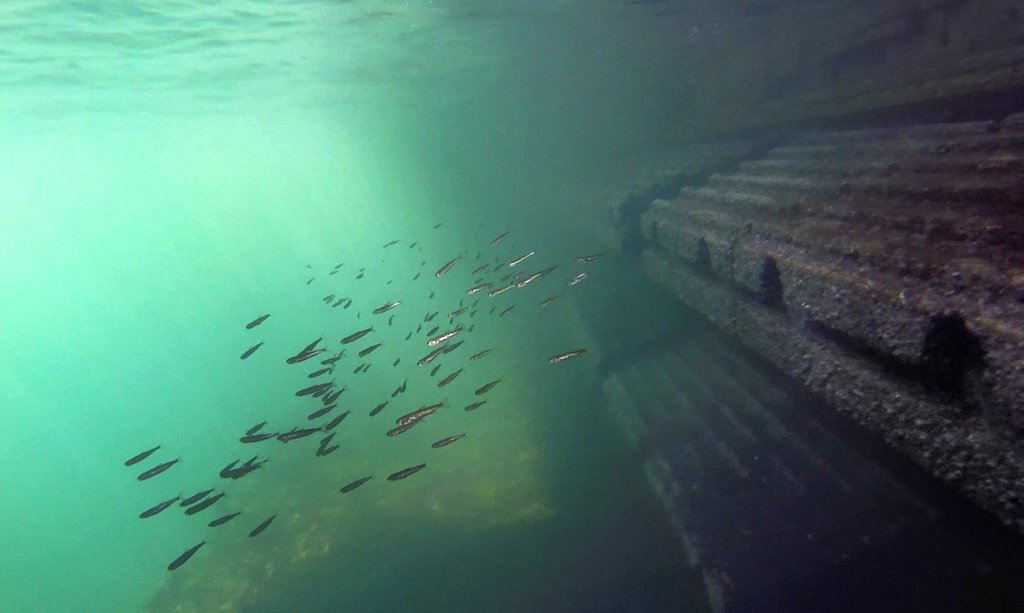

The new Seattle seawall is nothing like a natural shoreline, of course, but it might offer the fish more food and protection from predators than what they had before, according to monitoring studies. The improved habitat might just bridge the gap between places with more natural conditions along their migration route.

An animation produced as a student project in 2013 shows one problem with solid seawalls and bulkheads: the exposure to predators. The video, shown on this page, was done by Beryl Allee and John Summerson for a NOAA Fisheries program called “Bridging art with science to protect salmon habitat.”

If habitat improvements can be made along a solid wall, as in Seattle, there’s no telling what improvements might be made along less damaged stretches of Puget Sound shoreline. Work done previously at Olympic Sculpture Park (PDF 1.5 mb) north of the new seawall appears to offer some additional refuge for the migrating salmon, many of which are coming out of the Green/Duwamish River.

As I describe in the story, researcher Kerry Accola has used sonar to describe the behavior of salmon as they swim along the Seattle seawall. Stark shadows still seem to slow their progress, but the problem has diminished since glass blocks were installed to transmit daylight under the piers.

At night, the glass blocks convey artificial light from the bustling city streets above. I can’t help but wonder if that artificial light might be impeding the nightly progress of the salmon, which seem to swim faster at night. I’m not sure of the logistics, but an interesting experiment might be to cover the glass blocks at night to see how the fish respond.

The use of sonar to monitor juvenile salmon migration might someday provide important behavioral data along the entire migration route in Puget Sound. That would be one way to identify and eliminate the worst impediments encountered by each species of salmon.

Howard Hanson Dam

Meanwhile, improvements for downstream fish passage at Howard Hanson Dam on the Green River are expected to increase the number of juvenile salmon migrating through Seattle. The Army Corps of Engineers, which owns the dam, has agreed to move forward with a design for a fish-passage structure, as called for in a biological opinion from NOAA Fisheries. A new fishway for downstream migration is needed to avoid a jeopardy ruling under the Endangered Species Act, the agency said.

The fish-passage project would open about 100 miles of high-quality stream habitat for spawning and rearing by threatened Chinook and other species, according to a news release from the Corps.

“We’re optimistic that new fish passage at Howard Hanson Dam, with continued habitat restoration in the more developed lower and middle Green River, will boost fish populations toward recovery,” said Kim Kratz, assistant regional administrator for NOAA Fisheries. “That will, in turn, support tribal treaty fishing rights and benefit critically endangered southern resident killer whales.”

I don’t think we’ll have a good estimate of cost until the new design is complete, but it is expected to be upwards of $100 million.

Many of the fish that emerge from the newly accessible habitat will eventually pass by the Seattle waterfront, offering further justification for the improvements made there. The same goes for other Puget Sound shorelines. By the way, very few Chinook streams exist on the Kitsap Peninsula, yet the entire shoreline is considered critical habitat for Puget Sound Chinook. (See map of freshwater and saltwater critical habitat for Puget Sound Chinook produced by NOAA’s Environmental Response Management Application.)

A new “net-gain” policy

My story about the seawall also discussed a proposal to change the state policy of “no net loss” of shoreline function to a policy of “net gain.” How that might work will be the subject of a study by the Washington Academy of Sciences.

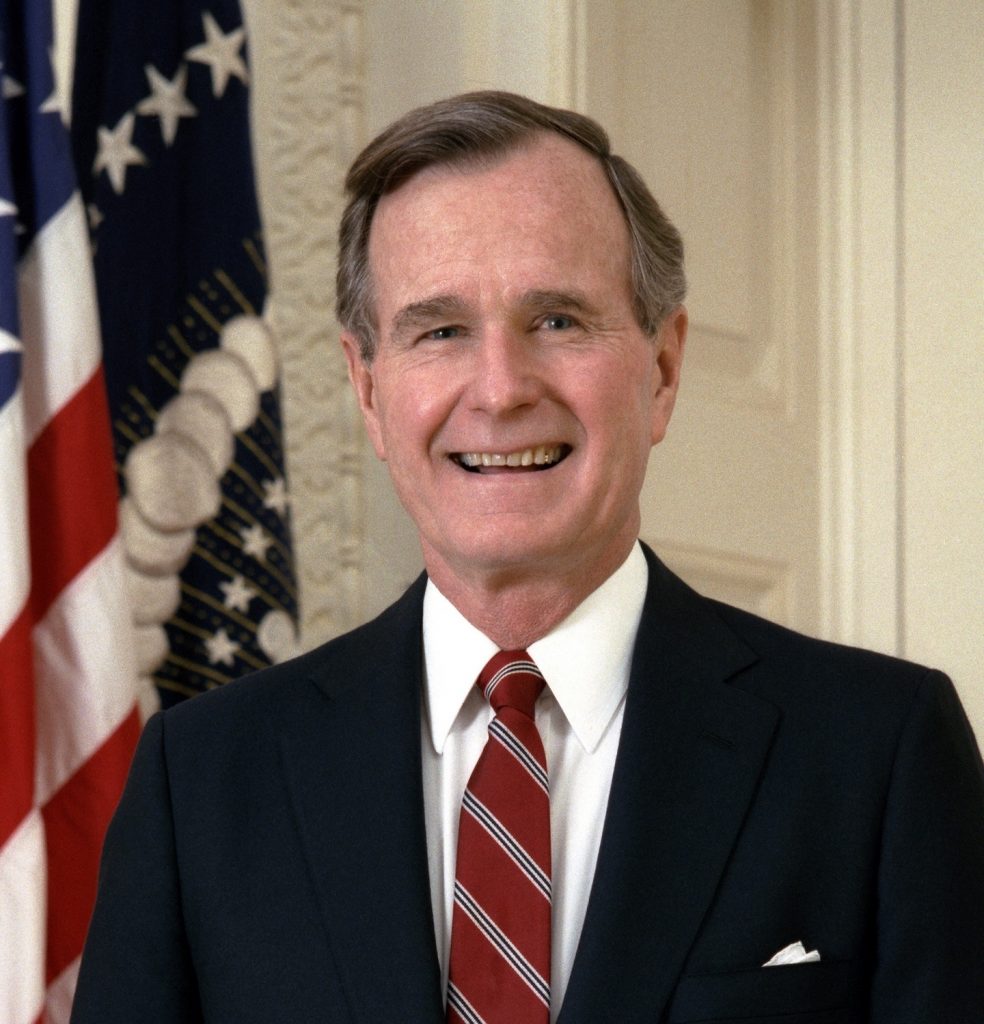

The term “no net loss” originates not with shorelines but with wetland conservation efforts under the George H.W. Bush administration in 1989. For years, wetlands had been filled and drained at an enormous rate — nearly a half-million acres per year nationwide — causing an alarming loss of fish and wildlife habitat.

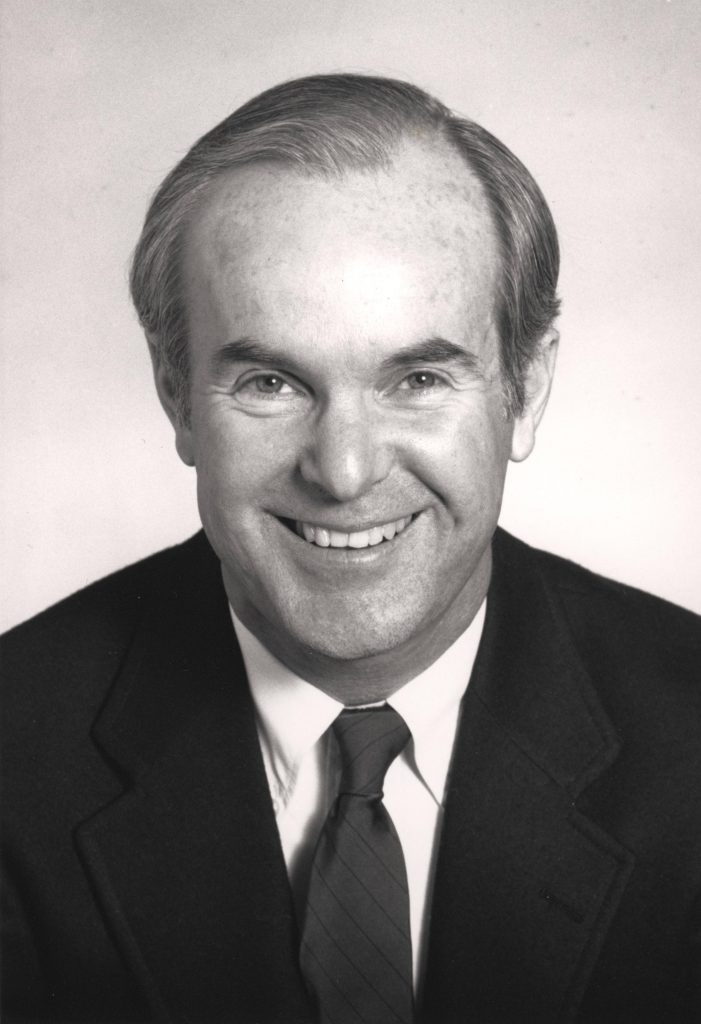

A 20-member National Wetlands Policy Forum was convened to address the problem. The group included three governors, among them Washington state Gov. Booth Gardner. One of the many recommendations of the forum was to stop the bleeding with a national policy of “no net loss of wetlands.”

The goal was announced during a speech that President Bush, an avid hunter, delivered to a convention of Ducks Unlimited on June 8, 1989:

“I want to ask you today what the generations to follow will say of us 40 years from now. It could be they’ll report the loss of many million acres more, the extinction of species, the disappearance of wilderness and wildlife; or they could report something else. They could report that sometime around 1989 things began to change and that we began to hold on to our parks and refuges and that we protected our species and that in that year the seeds of a new policy about our valuable wetlands were sown, a policy summed up in three simple words: “No net loss.” And I prefer the second vision of America’s environmental future.”

From those goals, four federal agencies moved forward to develop a coordinated wetlands delineation manual for protecting wetlands under federal law.

Before 1989 was over, Gov. Gardner established through executive order an interim goal of “no net loss” of wetlands. He added a long-term goal to “increase the quantity and quality of Washington’s wetlands resource base.”

The following year, he issued another executive order with more detail about how to mitigate for lost wetlands. The original “no-net-loss” directive still stands, though it was never codified into state rules. But the second directive was later expanded into our current rules for wetlands under the “critical areas” section of the Growth Management Act.

In 2003, when new rules came out to protect Washington’s shorelines, the concept of “no net loss of ecological functions” was incorporated into the actual regulation, codifying “no net loss” for the first time in Washington state. See the explanation in the “Shorelines Master Program Handbook” (PDF 724 kb) by the Department of Ecology.

The concept of “net ecological gain” is one that has been debated in England, where it has taken hold in some municipalities under a national goal of increasing “natural capital” over the next 25 years. Read the position paper by the Environmental Industries Commission.

England has embraced the concept of “leaving the environment in a better state for the next generation” and is working on ways to implement the idea, as described in the position paper.

In Washington state, the net-gain concept was advanced by the governor’s Southern Resident Killer Whale Task Force. Rep. Debra Lekanoff, D-Bow, a member of the task force, proposed a bill (HB 2550) to make “net gain” a formal policy of the state. Her fellow lawmakers, faced with many unanswered questions, agreed to conduct a $256,000 study to see how “net gain” might become incorporated into state law.

The Puget Sound Lowlands Ecoregion is important, unique and heavily urbanized. We need to do a better job of managing our urban watersheds especially the many stream estuaries which somehow are endlessly overlooked. The City of Olympia sits on 160 miles of stream-in-a-pipe and refuses to discuss daylighting any of it.