UPDATE, FRIDAY, JULY 2:

K pod arrived in the San Juan Islands yesterday, so the wait is over for the Southern Residents to arrive this summer. The whales came south through Rosario Strait yesterday morning, according to reports, and then they traveled along the south side of Lopez Island and over to the west side of San Juan Island. How long the K pod whales will stay in inland waters — and when they might be joined by J and L pods — is anyone’s guess. (See “Orca census” below, and report from Center for Whale Research.)

—–

Captured on video from drone (2019): A 4-year-old female orca named Kiki (J53) slowly circles and weaves through the water as a younger female, Tofino (J56), swims closely behind her and then alongside her before gliding up face-to-face.

Such intimate contact might be expected if the whales were close relatives, but that’s not the case — other than both orcas being members of J pod.

While social bonds among the Southern Resident killer whales appear to be complex, they are not random, according to researcher Michael Weiss of the Center for Whale Research, who used an unoccupied aircraft system (drone) to record more than 800 such encounters and then quantified his observations with statistical analysis.

Michael found that numerous whales — generally of the same sex and close to the same age — have formed enduring social bonds that could be described as friendships.

“These are strong social relationships,” he said. “I wouldn’t hesitate to describe them as friendships.”

His findings about orca relationships were reported June 16 in “Proceedings of the Royal Society — Biological Sciences.”

How these relationships affect the orcas’ hunt for food, energy conservation and ultimately survival may one day be determined through close observations, such as with drones. Aerial videos allow researchers to observe orca behaviors taking place underwater as well as on the surface — and with greater precision than using traditional boat-based platforms.

A few years ago, at least some of the Southern Resident orcas — now numbering 75 — would have been swimming through the San Juan Islands by this time of year. They would be hunting for spring Chinook salmon returning to the Fraser River and streams in Northern Puget Sound.

As of today — census day for the Southern Residents — the whales are still away, probably because the salmon runs are now dangerously low. For the latest news about their present locations, read on to the section “Orca census” below.

In the video mentioned above, an older male, 9-year-old Notch (J47) seems to be standing by and watching, a behavior that researchers sometimes describe as “babysitting.” The youngest whale in the video, Tofino, was less than a year old when the video was shot near San Juan Island, yet her mother is nowhere to be seen when the clip begins.

Suddenly, the missing mother, 24-year-old Tsuchi (J31), swims up powerfully from the depths and into the center of the video frame while carrying a fish in her mouth. Tofino wastes no time getting close to her mother. She sticks like glue to Tsuchi, who swims away rapidly while biting the fish in half and leaving some of the food for the trailing whales.

Social structure of orcas

From the earliest days of orca research, scientists have known that killer whales live in matriarchal societies, in which individual whales generally stay with their mothers for life. Family groups, led by elder females, may consist of several generations. These groups are called matrilines, with members tied together by blood and tradition.

Image: Michael Weiss

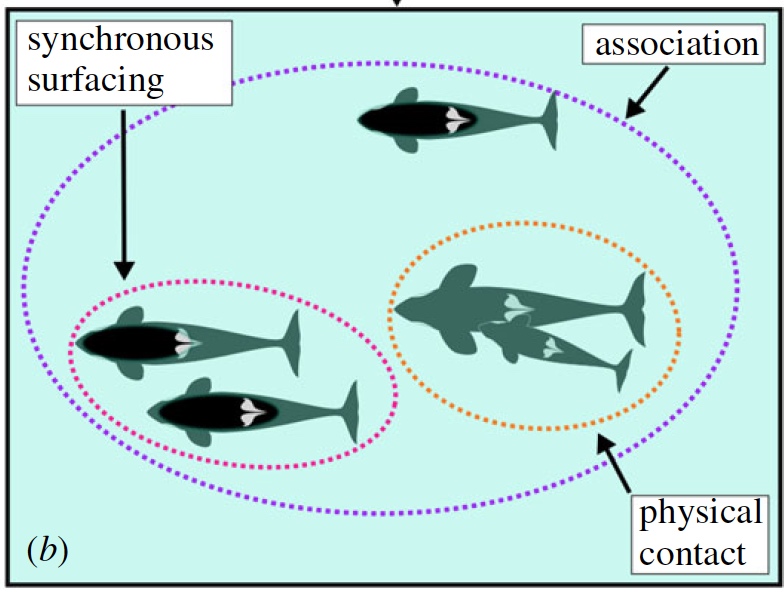

J pod, the subject of Michael’s study, consists of multiple matrilines that often travel together and share a common vocal dialect. The goal of the study was to measure the social connections between members of different family groups, as well as those within the same group. Based on years of observation, the research team decided to focus attention on three types of interaction:

- Association, in which groups of killer whales are seen together, providing the opportunity for interaction;

- Physical contact, in which the whales come close, often with extensive touching that could result in tactile, possibly emotional, responses; and

- Synchronous surfacing, in which the whales move together, surfacing and blowing at the same time, sometimes even moving left and right as one.

Over a period of 10 days on the water in 2019, a total of 10 hours of video footage was shot from a drone (DJI Phantom 4 Pro V2) at an altitude of 100 to 400 feet and positioned to the side or behind the whales to avoid disturbance. The drone, launched from a 21-foot research boat, was flown by licensed pilots under federal permits.

As expected, the most common associations were observed among family members. Less predictably, the researchers found that females and especially young whales seemed to play a central role within the groups, as observed by the physical contact of whales gathered together. In general, the older the whale, the less socially connected.

The relationships among individual whales became quite noteworthy. This was something discerned by observing the contacts of every animal, not by looking only to see which whales were grouped together.

Why males tend to be more distant from the observed groups is open to speculation, but one idea is that the larger males must spend more time foraging to meet their energy needs. On the other hand, young animals may find their energy needs met by nursing or by receiving fish from their elders, giving the youngsters more time to socialize.

Like other social mammals

The social interactions among members of J pod has led to comparisons with other social animals, including humans and other primates. For example, the whales were seen to become less social with age, a trait observed in observations of great apes. Humans and orcas are among the relatively few species that remain active and influential past their reproductive lives.

Researchers may eventually find that touch among the whales has evolved into psychological benefits, as it has in humans, although such benefits are not always easy to measure.

“It feels nice to interact with our friends,” Michael said, “and touch gets a lot of good brain chemicals going. Ultimately, social interactions are important to a sense of trust, in finding food and in survival itself.”

Beyond the social aspects of these findings, the study suggests that young and female orcas may be involved in more synchronous surfacing as well as direct contact with each other, raising the specter of disease transmission. As Michael Weiss showed in a previous study, the effects of disease could be devastating to the Southern Residents. See Encyclopedia of Puget Sound, March 10, 2020.

The drone research builds on years of study by the Center for Whale Research, led by Ken Balcomb, who told me that he has observed these kinds of social interactions while watching the whales through the years. The beauty of Michael’s study, he said, was the creation of a statistically relevant set of observations that can be tested over time.

Darren Croft, a co-author of the study, credited CWR for its 45 years of work with the orcas. Darren is affiliated with the Centre for Research in Animal Behaviour at the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom, where Michael earned his doctorate degree last year.

“This study would not have been possible without the amazing work done by CWR,” Croft said in a news release. “By adding drones to our toolkit, we have been able to dive into the social lives of these animals as never before.

“In many species, including humans, physical contact tends to be a soothing, stress-relieving activity that reinforces social connection,” he continued. “We also examined occasions when whales surfaced together — as acting in unison is a sign of social ties in many species. We found fascinating parallels between the behavior of whales and other mammals, and we are excited about the next stages of this research.”

Other questions to study

Although 10 hours of video accumulated from short segments seems like a lot, it is not enough to draw conclusions about more subtle social behavior, such as the sharing of food and cooperation in chasing down fish, Michael said. These critical behaviors may be based on social relationships, but they are rarely seen.

On the other hand, aggressive behaviors, including rare incidents of biting, may also be important clues to the social relationships among whales, he said. Many more hours of drone video may be needed to further the understanding of all sorts of social interactions, he added.

Previous reports have discussed the importance of collective knowledge among the whales, including the memory of where to find food when the salmon runs are small. Social bonds, as shown in these studies, could play a role in how older whales teach the younger ones to survive. See Encyclopedia of Puget Sound, April 2, 2019.

Some of the most interesting findings are related to the individual relationships between unrelated orcas, as seen in the drone footage.

“There’s J49 and J51,” Michael said, referring to a 9-year-old male named T’ilem I’nges (pronounced Teelem Eenges) and a 6-year-old male named Nova. “In the drone footage, they can’t get enough of each other.”

It turns out that young male friends are fairly common among the whales in J pod, he said, adding that any future competition for females probably will be “indirect” without much conflict between them.

Other researchers involved in various aspects of the drone project are affiliated with the University of Washington, Seattle; University of York, UK; and Institute of Biophysics, Italy. The study was partly funded by the Natural Environment Research Council in the UK.

Orca census

For the third year in a row, the Southern Residents failed to return to Puget Sound before the annual orca census date of July 1. For many years, one or more of the pods would be seen swimming through the San Juan Islands and into southern Strait of Georgia in Canada as early as mid-May.

The last sighting of Southern Residents in Puget Sound was on April 10, when J pod was observed in San Juan Channel on the east side of San Juan Island (Center for Whale Research encounter.) They have not returned since, even though J pod typically comes and goes more often than the other two pods.

The date of the Southern Residents’ arrival for the summer seems to come later and later each year, said Ken Balcomb, who maintains the census under a contract between the federal government and his Center for Whale Research.

This year’s census is likely to include three orca babies, including two J pod calves born last September — too late for last year’s count. The new whales are Crescent (J58), a female born to 16-year-old Eclipse (j41), and Phoenix (J57) a male born to 23-year-old Tahlequah (J35). If you recall, Tahlequah became famous and touched the hearts of many people in 2018 when, in apparent mourning, she pushed her dead calf around for 17 days.

The two newest calves in J pod appear to be healthy and strong, Ken told me, referring to the April 10 encounter report from CWR’s field biologist Mark Malleson.

As Mark wrote in his report, “The whales were in one large, loosely spread group traveling very slowly to the point of going pretty much nowhere. J57 and J58 were enjoying themselves while playing with one another.”

The last unofficial report of J pod was this past Friday near Tofino, off the West Coast of Vancouver Island in Canada, as reported with photos to Orca Behavior Institute.

The third calf to be added to this year’s census will be L125, born to 30-year-old Surprise! (L86) in February. While there are no recent reports of the mother-calf pair, there is no reason to believe that they are missing, according to Ken, who is waiting for further reports of L pod.

Mark Malleson got a look at some of the L-pod whales in an encounter June 7 near Swiftsure Bank at the mouth of the Strait of Juan de Fuca in the Pacific Ocean. Because of rough water, he and observer Joe Zelwietro were unable to see all the whales that may have been present. It is also possible that Surprise! and her calf were elsewhere.

The unnamed L-pod calf is about to get a name from The Whale Museum in Friday Harbor, which conducted a public vote on three possible names for the offspring of Surprise!. The choices were Confetti, Current, Element (as in Element of Surprise!) and Eureka!. The announcement of the name could come as early as today.

UPDATE: The latest whale in L pod has been named Element, based on the voting.

A group of whales tentatively identified as K pod was spotted yesterday in Knight Inlet near Johnstone Strait between Vancouver Island and the mainland of British Columbia. If the whales are indeed K pod, they could be headed south into U.S. waters, Ken told me, referring to past experiences with those animals. Will they be the first Southern Residents to make an appearance this summer? We will know soon, and I will update you in this space.

Because the three pods of Southern Residents have not been seen long enough to conduct a proper survey, it is possible that other new calves may show up with the pods. It is also possible that a complete survey could reveal that one or more whales are sadly missing, but any presumption of death would likely wait for several additional sightings. With luck, we will be able to report that all the whales have survived for another year.

Check out Our Water Ways, as posted on last year’s census date, and later in September when the final tallies were made for the federal government,

Based on the best available information, there are now 75 orcas in the three Southern Resident pods — not including Lolita, also known as Tokitae, who was taken from Puget Sound and now lives at the Miami Seaquarium. J pod contains 24 whales, K pod 17, and L pod 34.

Steep population declines since 1996, when the Southern Resident population stood at 97, led to their listing as an endangered species in 2005. For information about recovery efforts, check out NOAA’s website on the Southern Residents.

No Comments yet!