As Americans, we have become all too familiar with the spread of a deadly virus and the terrible consequences of a delayed response to an outbreak. As a result of our experience, I’m wondering if some of us might have a more visceral sense about the need to control invasive species.

I’m not saying that the ecological, economic and cultural disturbances wrought by invasive species are on par with a massive loss of human life. But the common denominator is a biological perturbation that occurs suddenly and threatens to expand rapidly out of control, leaving permanent damage. The ultimate outcome depends on reaction to the threat.

“In the invasion world, early detection and rapid response is the best way to manage invasive populations,” said Emily Grason, a marine ecologist with Washington Sea Grant. “That’s similar to a pandemic. You want to find outbreaks when they are small and then react very quickly.”

Emily manages Sea Grant’s Crab Team, a group of more than 200 volunteers and professionals who systematically set crab traps in bays and estuaries to locate early infestations of the European green crab. This small crab, considered one of the world’s most damaging invasive species, has taken over bays on the East Coast, disrupting natural conditions. When a green crab is caught in Puget Sound, the first effort is to rapidly deploy many more traps to assess and reduce the crab population before it grows out of control.

Emily describes several ways that reactions to an invasion of nonnative species may resemble a pandemic — such as communicating the risks to the public and political leaders, determining priorities for action with limited resources, and enlisting the help of enough people to stay ahead of the threats.

“We don’t want to be flippant about this comparison,” Emily told me. “Human lives are at stake in a pandemic, and there are real differences in the immediate and long-term consequences.”

While not a direct threat to human health, European green crabs could take a heavy toll on native shellfish, destroy eelgrass beds important to salmon and forage fish, and consume commercial clams and oysters with financial losses to the shellfish industry. The Legislature has awakened to the threat with increased funding in recent years, as lawmakers also invest in battles against other invaders — from zebra mussels that could clog up critical water pipelines to Asian giant hornets that threaten to wipe out honey bee colonies.

Meanwhile, there is no letup in the 47-year effort to hunt down and destroy gypsy moths, which could defoliate trees by the thousands if the invasive moths ever gain a foothold in this state. The gypsy moth program is run by the Washington State Department of Agriculture. See also “Priority Species,” Washington Invasive Species Council.

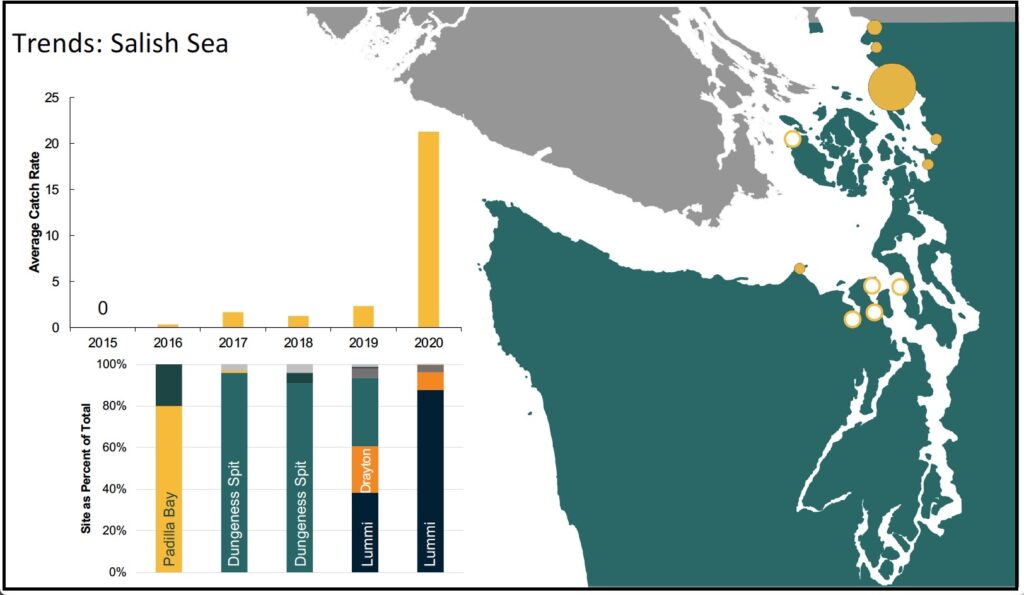

The volunteer search for European green crabs in Puget Sound actually started with limited surveys more than 20 years before the first green crab was spotted on San Juan Island in August of 2016. Washington Sea Grant had taken over formal management of the program the year before — in 2015 — after green crabs had established a breeding population in Sooke Basin, west of Victoria, B.C. That Canadian site is just across the Strait of Juan de Fuca from Washington’s Dungeness Spit.

In August, it will be five years since the beginning of the Puget Sound invasion, and I asked Emily what she has learned along the way. One thing, she said, is the “value of doing your homework,” such as checking out all your assumptions.

For example, it was once assumed that the Puget Sound invasion began with crab larvae drifting across the Canadian border from the infestation in Sooke. But genetic studies revealed that the population on the Dungeness Spit was far more similar to green crabs found along the Washington Coast. With that in mind, researchers were able to connect that invasion to occasional oceanic currents that flow inland along the south side of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, opposite to the normal outflow. Such “reversals” are capable of bringing crab larvae into Puget Sound, although Canadian crab populations appear to be the source for some invasions on this side of the border.

“How green crabs were getting into the Salish Sea was not expected,” Emily said. “That reminds me that it is always worth checking our own assumptions to make sure that we are doing the right thing.

“When people talk about invasions, the only surprising thing is when there are no surprises,” she added. “Surprises are the rule, not the exception.”

Emily says she has also learned the value of meaningful collaborations. With respect to green crabs, many experts from a variety of agencies as well as community members have contributed knowledge, innovations and new ideas to the effort of protecting the Puget Sound ecosystem.

“No one person is better situated than another,” she said. “If you’re not talking and working together in good faith, you risk missing something and not seeing the full picture.”

While the pandemic blunted the Crab Team’s efforts and put volunteer recruitment on hold last summer, more than 90 percent of the identified trapping areas were covered through an intensified effort of team members following strict pandemic protocols (Salish Sea Currents, May 21, 2020). More than 11,000 traps were deployed, as team members also confronted a relatively new invasion discovered during the fall of 2019 in Drayton Harbor, a mile south of the Canadian border.

A new management team, led by Chelsey Buffington of the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, captured 255 crabs in Drayton Harbor last year. That’s more green crabs than the total captured at all the inland sites the previous year.

“All of the mud slogging and crab wrangling was done almost exclusively by the three dedicated crew members: April Fleming and Lindsey Parker, seasonal technicians with Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, and Allie Simpson, the local coordinator of the effort working with Northwest Straits Commission,” Emily wrote in her extensive Crab Team Blog post at the end of the year.

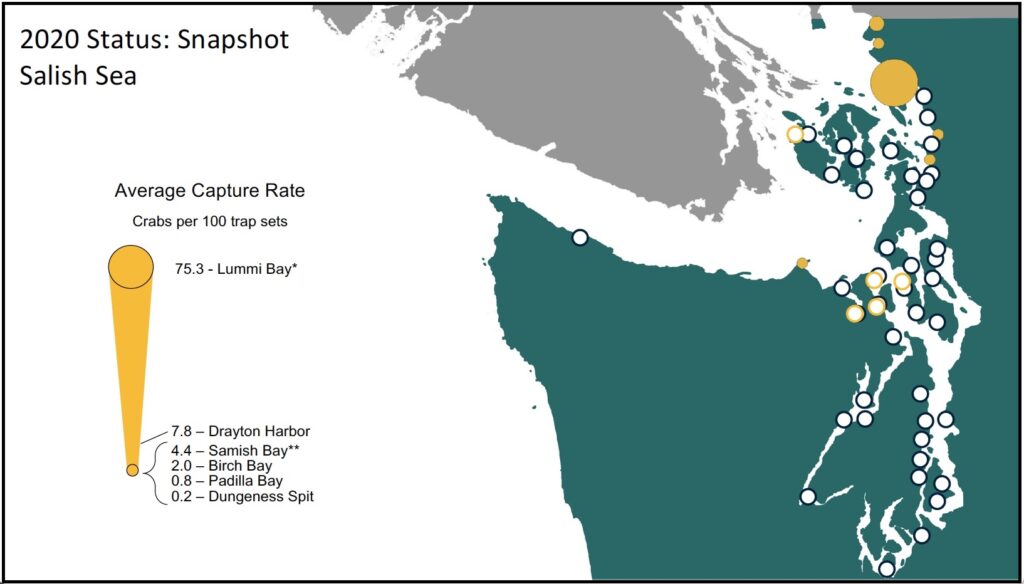

A key finding was that green crabs in Drayton Harbor were concentrated in a few locations, rather than being dispersed throughout the harbor. Now the hope for Drayton is that it will follow a pattern that has apparently created a favorable trend for Dungeness Spit. There, a heavy trapping effort over three years reduced a large number of crabs down to just three caught last year in 1,883 trap sets.

An even larger infestation last year was seen in Lummi Bay near Bellingham (south of Drayton Harbor), where crabs were first discovered in 2019. The population growth in Lummi Bay was so rapid that a trapping effort, led by the Lummi tribal biologists, caught more than 2,500 green crabs last year. That includes a large number of younger crabs that showed up in August and September. Most of the crabs were caught within a 750-acre sea pond, an artificial water-impoundment used to support nearby salmon and shellfish hatcheries.

“The sea pond appears to be, in some ways, a nearly perfect incubator for green crabs,” Emily said in a story published in Northwest Treaty Tribes magazine. “The enclosure protects the site in such a way that it creates conditions we don’t really see on that large of a scale anywhere else. It’s quite shallow but retains water all of the time, and it’s very protected from a lot of other conditions that might make it hard for green crabs to survive.”

Volunteer training resumed this year, with the trapping effort underway in early April. So far, a relatively few crabs have been caught in Drayton Harbor, Dungeness Spit and Samish Bay.

Related stories:

- Story map: European green crab in Puget Sound, Washington Sea Grant, Puget Sound Institute (2017)

- Invasive stowaways threaten Puget Sound ecosystem (2016), published less than a month before the invasion was discovered

- Building a baseline of invasive species: The Puget Sound Expedition

No Comments yet!