As Washington state regulators contemplate a ban on the chemical BPA from food and drink cans, a manufacturers organization insists that BPA has already been removed voluntarily from nearly all food cans.

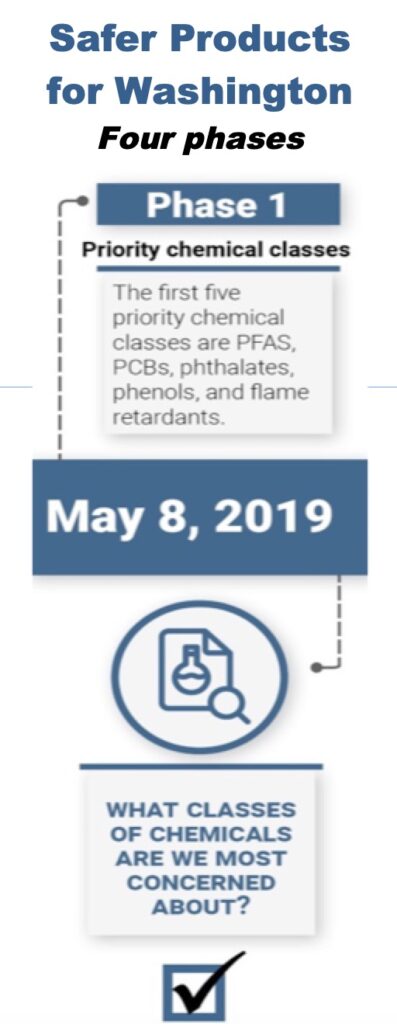

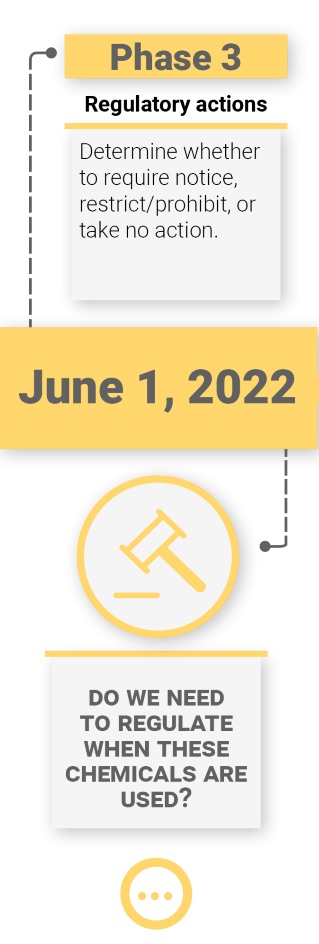

Washington Department of Ecology is engaged in Phase 3 of the Safer Products for Washington program, which is evaluating five groups of chemicals known to cause health effects. Agency toxicologists are studying whether safer alternatives are practical and should be required as a matter of state law.

One of the compounds under review is bisphenol A (BPA), which can interfere with hormonal functions in humans and animals and affect development and reproduction. The chemical was once widely used as a coating on the inside of food and beverage cans to resist corrosion. Although the federal Food and Drug Administration has declared the chemical safe at common exposure levels for adults, there is a lot more to this story, as I have described in a series of blog posts, including Watching Our Water Ways in 2019 and Our Water Ways in July of last year.

As Ecology considers safer alternatives, the Can Manufacturers Institute, a national trade organization based in Washington, D.C., responded with a laboratory study of 234 sample cans containing various food products purchased at stores in Seattle and Yakima. Only two imported products being sold in Seattle were found to contain BPA in the ends of the cans: coconut milk from Thailand and peaches from Australia.

That’s a dramatic change from similar surveys conducted just a few years ago, including the 2016 Buyer Beware report (PDF 5.2 mb) by the Breast Cancer Fund, which found that about two-thirds of the cans tested contained BPA.

Because of consumer demand, the voluntary transition away from BPA is nearly complete, and Washington consumers face no significant exposure to bisphenols from eating canned foods, according to Sherrie Rosenblatt, spokeswoman for the Can Manufacturers Institute.

“We continue to urge (Ecology) to remove food cans as a priority product associated with exposure to bisphenols from its Safer Products program,” she said in an email. Check out CMI’s full comments.

Behind the scenes, there is kind of a skirmish going on over possible replacement chemicals — and industrial espionage is part of the intrigue. But let’s first touch on what is happening in Washington state.

If the latest survey of BPA in canned foods is confirmed, it is good news for the consumer. One could argue that there is now no need for new regulations to ban BPA. On the other hand, considering what appears to be a new stance in the industry, one could argue that a ban would provide legal assurance of greater safety with no significant harm to the vast majority of can manufacturers or to the food industry as a whole. The law does not require testing or reporting.

Since CMI found BPA in two cans imported from other countries, we have to wonder if the phase-out will eventually be complete or if foreign sources of canned foods may always pose some risk.

As part of an increased effort to improve environmental justice, Ecology officials are trying to make sure that disadvantaged populations, such as low-income or certain ethnic groups, are not affected more than others. Early studies showed that low-income populations were more prone to higher exposures to BPA, in part because of their greater consumption of canned foods. (See Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology, 2006.)

Ecology officials are still evaluating their options as part of Phase 3 of the Safer Products process. The CMI report provides helpful information, but it isn’t a formal, peer-reviewed study. As such, it cannot be considered as formal evidence in the decision-making process, according to Ecology officials. If nothing else, the report shows that alternative chemicals are available.

The Breast Cancer Fund, which produced the 2016 Buyer Beware survey of BPA in canned food, expressed support for the apparent phase-out of BPA, as determined by the Can Manufacturers Institute. But the fund bemoaned the lack of explicit information about which chemicals are being substituted in particular products.

“Identifying the safety of BPA alternatives is challenging, given the insufficient FDA review and approval of packaging additives and highly protected trade secrets in this product sector,” states a fact sheet (PDF 469 kb) from the organization.

The study by the Can Manufacturers Institute used infrared spectroscopy to identify the chemicals associated with can linings from a variety of food products. Some cans had no lining. Other linings involved acrylic, polyester or vinyl compounds as well as epoxy-based linings made with or without BPA.

Not included in the CMI’s analysis, however, were drink cans, which appear to present a special challenge because they are made from aluminum rather than steel. But a breakthrough by scientists at Valspar — now a subsidiary of Sherwin-Williams — offers hope that BPA-free liners could soon be widely available for drink cans as well, according to an article in Chemical & Engineering News.

“Rather than look in the toolbox of epoxy alternatives for food and beverage cans, Valspar sought to develop a new epoxy without using monomers that affect the endocrine system,” states the article by Melody M. Bomgardner. “Now, after a decade of effort, Sherwin-Williams is commercializing a new can-lining epoxy, built from the ground up with a new monomer. The company says it is safe and performs just like those made with BPA.”

The new epoxy, called valPure V70, is used in many beverage cans in California and elsewhere. Although not identified specifically, this non-BPA epoxy may well have been seen in the steel cans tested by CMI in Washington state.

In her article, Bomgardner describes how scientists searched for, discovered and eventually tested a chemical replacement for BPA that was not biologically reactive. That chemical, tetramethyl bisphenol F, is being studied in labs across the U.S. and is under review by advocate groups.

Other available products coming on the market include metal coatings that use acrylic or polyester resins, such as Toyochem’s new Lionova brand.

The competitive rush to find acceptable replacements for BPA in drink cans involves some major players, including Coca-Cola. How much is at stake can be gleaned from the story of chemist Xiaorong “Shannon” You, who was recently convicted of stealing trade secrets that prosecutors valued at $120 million. She was said to be negotiating a deal to share chemical information with Chinese partners, as described in a story by Craig Bettenhausen in Chemical & Engineering News.

How these new can coatings will affect regulations in Washington state is yet to be seen, but a major part of the Safer-Products-Phase-3 effort is to decide — as the name implies — whether safer chemicals are available for use in food and drink cans. That would involve a review of the studies focused on the various alternatives, including new products certified for safety and performance by Cradle to Cradle and other certificate programs.

An interesting aspect of the Washington law is that regulators need not establish a threshold for human safety, such as the FDA has done. After determining that a chemical can cause harm, the question becomes whether a safer chemical is “feasible and available” before considering regulations. The process for determining whether an alternative chemical is safer is outlined in a working draft of “Phase 3 Criteria for Safer” (PDF 954 kb).

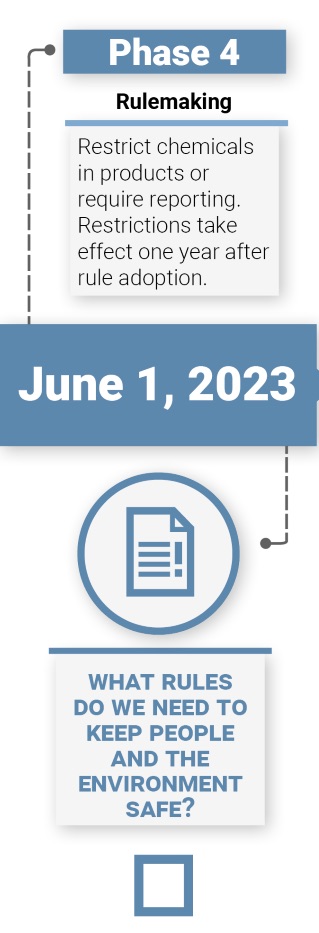

A webinar to discuss the issue of chemicals used in food and drink cans is scheduled for July 13 and is open to anyone interested. Also on the agenda that day is the use of flame retardants in recreational polyurethane foam and potential substitutes. Visit the registration page and sign up to take part. A draft of the Phase 3 report is expected by the end of this year, with a final report due on June 1 of next year, followed by potential new rules coming out the following year.

In addition to food and drink cans, people may be exposed to BPA by handling those slick receipts made with thermal paper containing the toxic compound. The chemical is absorbed through the skin, and hand sanitizers have been shown to increase the absorption and exposure. (See 2014 study in PLoS One.) Retail clerks and checkers who handle a lot of receipts are considered the most at risk.

The Phase 2 report from the Safer Products team at Ecology covers those issues surrounding thermal paper, as well as all the products of concern identified among the first set of priority chemical classes:

- Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)

- Phthalates

- Organohalogen flame retardants and flame retardants identified in RCW 70.240.010

- Phenolic compounds

- Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)

The draft Phase 3 report from Ecology, scheduled for the end of this year, could signal some important changes to consumer products, with powerful implications across the country.

No Comments yet!