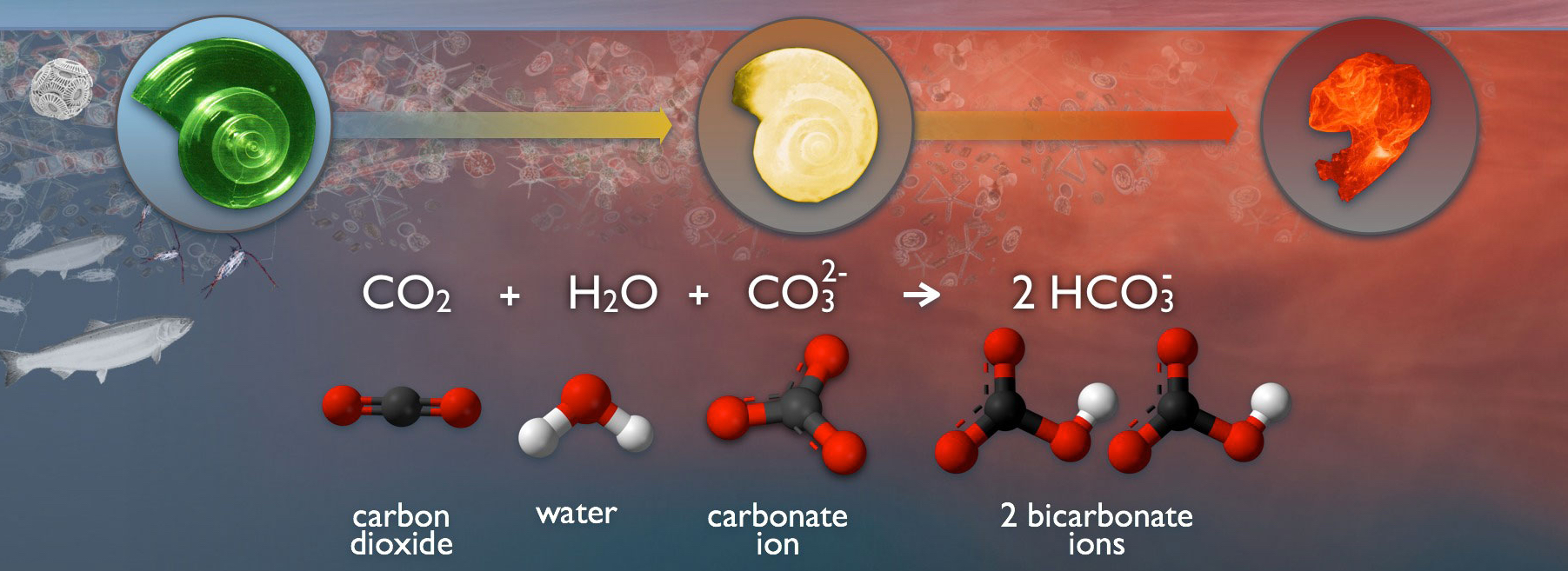

It was fairly alarming, even to scientists, to hear the latest research regarding ocean acidification — a powerful change in ocean chemistry that results from excess carbon dioxide passing from the atmosphere into the oceans of the world.

One of the most alarming reports came from Richard Feely, senior scientist at NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle. Dick talked about how changes in ocean chemistry will soon accelerate, with damaging consequences, as the ocean’s buffering capacity begins to break down.

Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

It’s all a bit technical, but I worked carefully with Dick and other scientists to find ways to explain their findings, so that average people can gain some insight into the oceanic changes taking place. Check out “Rate of ocean acidification may accelerate, scientists warn,” a story I wrote for the Washington Ocean Acidification Center at the University of Washington and republished in the Encyclopedia of Puget Sound.

It turns out that, because of ocean currents, some of the most severe changes are taking place in the Pacific Ocean off the Northwest coast, and this issue of buffering capacity is something that should be getting more attention.

“If we continue down the road we are on, we will see very dramatic changes in the next 10 to 20 years,” Dick declared at last year’s Ocean Acidification Science Symposium in Seattle.

My story is organized by topic. If you are more interested in the biological effects than the chemical effects, then you can skip down to the sections about fish, crabs, plankton and vegetation, or environmental DNA, as researchers explain the effects of climate change and ocean acidification in our region.

I keep hoping that if people can read enough about ocean acidification and climate change, then they will better understand the problems our world is facing and demand changes sooner than later. I’m talking about personal choices as well as government actions.

Unfortunately, we all seem to be distracted by other things in our lives. Social media is filled with people expressing outrage about relatively trivial matters. While there is plenty of outrage flying around, the emotional impact can get pretty exhausting.

My hope is that people can set aside their emotions for a time and begin to deal with facts. I know it seems hard to separate fact from falsehood, but if one considers the sources of information and digs for the facts, I’m confident that reality will emerge.

I can’t help but wonder where we would be today if we had ignored the water-pollution crisis made famous when people noticed Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River on fire. Starting with the Clean Water Act in 1972, the crash program used federal funds to begin cleaning up our polluted waterways throughout the country. We are not done yet with the cleanup, but we can say that the entire ecosystem — including humans — is better off because Americans acted.

People could have blamed earlier generations for the pollution, but that would have served no purpose. Earlier generations simply assumed that our waterways — especially the oceans — could absorb all our pollution. Today, ignorance of climate change cannot be an excuse for lack of meaningful actions.

Trying to engage average people in climate change may not be as easy as addressing water pollution. Instead of seeing rivers on fire, we see forest fires and bush fires as the polar ice caps melt. The links from car exhaust to wildfires aren’t quite as direct as from sewage to water pollution, which is why we need to engage people in the discussion.

I often tell my children and grandchildren to make a list of “pros” and “cons” when it comes to making big decisions. You don’t need to disregard your feelings in the assessment, I tell them, but at least understand the benefits and the drawbacks of any action. So it is with the actions we can take to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In February, I pulled together some ideas for talking about climate change in Watching Our Water Ways.

Some would say my plea for fact-based decisions misses the emotional context that can drive people to action. Seeing animals dying in the fires would more likely move people, they say. Sure, videos of rescued animals and burned houses might get people’s attention, but it doesn’t help them understand what they can do.

UW oceanographer Jan Newton, a leader in the Washington Ocean Acidification Center, said helping people understand the science of climate change is important for a variety of reasons.

“The more people understand that this is not hocus pocus, the more there will be a groundswell for taking action,” she told me, adding that public support is critical to funding the scientific investigations that define the problems and help us survive the crisis.

While the basic concepts of climate change and ocean acidification are well understood, the finer details remain the subjects of fascinating studies and ongoing debates. Organizations such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change can describe issues that are largely settled as well as those still evolving. Check out the 2014 summary for policymakers (pdf 3.2 mb) as well as other reports (click “reports”) completed and in process.

The Washington Ocean Acidification Center and the Climate Impacts Group are both part of the UW’s EarthLab, a consortium of UW programs that “engages public, private, nonprofit and academic sectors in a shared and ongoing conversation that converts knowledge to action.”

The concept for EarthLab goes back a dozen years to the creation of the UW College of the Environment, but the institute has really begun moving the last year or so, as executive director Ben Packard explains in a statement issued last week.

Constance McBarron, communications and engagement lead for EarthLab, tells me that climate change and ocean acidification are a big part of a communications strategy to connect average people with scientific findings.

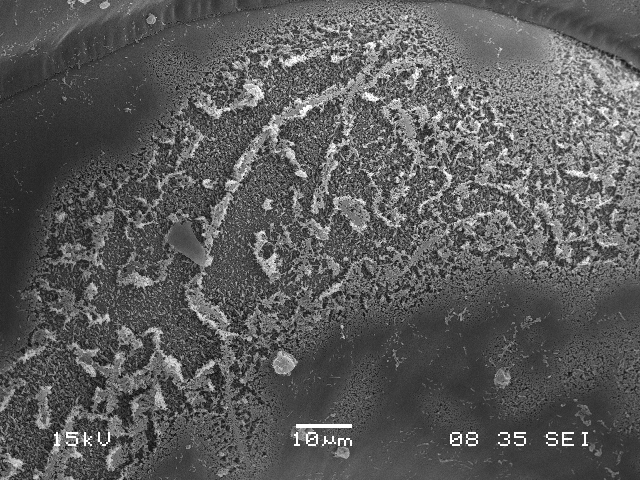

An article on the EarthLab website tells the history of the Ocean Acidification Center, which grew out of the governor’s Blue Ribbon Panel on OA. The story connects to a video about shellfish research, which has helped oyster growers respond to inhospitable waters affecting their shellfish.

EarthLab operates an Innovation Grants program, which will award up to six grants of $300,000 for “pressing environmental programs.” The grants effort “seeks to invest in teams of University of Washington researchers, students and non-academic partners developing innovative solutions to pressing environmental challenges.”

In the current request for proposals, the description states: “Pressing environmental challenges might include, for example: the effects of climate change on people and ecosystems, such as ocean acidification, increased food insecurity, and displacement due to sea level rise; environmental pollution or hazards disproportionately affecting indigenous communities, communities of color and low-income communities; the impacts of nature and the built environment on human health; the effects of reduced biodiversity on ecosystems and human well-being; and more.”

Climate change is complex, and it is taking place whether we are ready or not. Adapting to the changes and preventing more severe effects will be a challenge for us all. As Constance McBarron explained it, EarthLab’s goal is to provide a hopeful voice as well as real solutions to help us live through the crisis.